Dear Sir: Stuff It You Know Where--Reb MacRath

Enter the Zone of the Big Time Boo-Hoo. You've just received the report card for your latest book or whatever. And you've received a C or D...or even an E or an F. Suddenly the A's, B-Pluses and B's you've received have a pall cast over them. You feel slimed and vilified.

Then, by degrees, worse happens. You start to wonder if They're right...and end up feeling crushed.

Poor you. Life doesn't get too much tougher than becoming a poor crushed tomato. You envy hapless newbies who've earned their own rotten report cards. They'll grow as they go...or go under. But you? You're a veteran in the Arena and you've spent decades refining your craft. Still, you're receiving E's and F's for the very things you chose to do...and which you feel sure you've done well.

What to do?

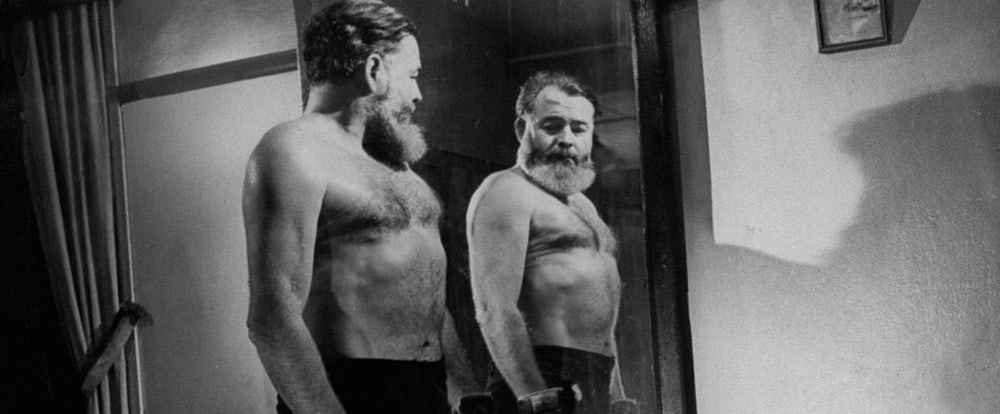

Hemingway wrote that if we believe the good things people say about our work, then we must believe the bad. But did he practice what he preached? After all, he did slap critic Max Eastman in the face with a copy of Death in the Afternoon.

It may have been truer to say that we must suffer bad reviews. Still, Gore Vidal thought otherwise:

In their youth most people worry whether or not other people will like them. Not me. I had the choice of going under or surviving, and I survived by understanding (after the iron- if not the silver- had entered my soul) that it is I who am keeping score. What matters is what I think, not what others think of me; and I am willing to say what I think. That is the critical temperament. Edmund Wilson had it, but almost no one else now does, except for a few elderly Englishmen.

Key points:

--We can go under or survive.

--We can better our chances if we start keeping superior score and become at heart elderly Brits.

--At all times we need to be clear in our heads about what counts artistically. Then we can filter our senseless attacks on our having done what we set out to do.

Key caveats:

--Ignoring all feedback is arrogance, not a sane alternative.

--Awareness of the motives or values of critics is the master key. (If Byron had listened to the friends who begged his return to his earlier style, he'd never have written Don Juan.)

--Consistency in feedback can offer useful clues. (Writers may develop 'tics', stylistic trademark habits. And they may not see how boring these tics have become: Tarantino's over-the-top use of the N word...or his patented 'cool' dialogue...in The Hateful Eight. Actors? Clearly, Tom Cruise listened, reining in his Boy Toy style for the last two MI films: the new gravitas is fitting for a star now in his fifties.)

The Boy Toy Tom The Tom who listened

--Hubris in scorekeeping can detract from one's own work. (Vidal had wicked verbal fun with his famous rivals. But he never wrote a masterpiece...as his chief victim, Truman Capote, was delighted to point out.)

The scorekeeper His chief victim

Parting thoughts:

--If we believe only our best reviews, we're prideful.

--If we refuse to chew upon enlightened feedback, we're fools.

--The most useful feedback is that which helps us grow.

--Now and then we'll always disappoint our loyal fans.

--But the burning question must always be:

Could this book that's caused their discontent be the best thing that I've done? Or: in this particular instance, who's the one keeping superior score?

Thanks to Valerie Laws for inspiring this post.

Comments

My wife and I did a revue show at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe for a few years in the late 70s. It got great reviews and full houses but, while I still have the recordings that prove people were enjoying themselves, the main things I remember are the occasional individuals sitting in a laughing audience with stony, bored faces. The logical response to that should have been that, since they were so clearly in a tiny minority, they were 'wrong' about their assessment of my material. But, perversely, that's not the way it works and I've no idea why. I think our responses to negative criticism are more complex than the motives of the people who articulate or demonstrate it.