All Those Funny Names... by Susan Price

|

| Elfgift by Susan Price |

I was once asked, in a school I was visiting, if I’d made up ‘all the funny names’ in Elfgift. The questioner had found them difficult to say and remember— and, of course, fantasy writers are prone to making up unpronounceable, funny names. — Jxxx!&gk, meet Slpadsim.

But no. The funny names in Elfgift may be hard to remember and pronounce but they are all real Anglo-Saxon names.

Ebba, the name of the slave heroine, means ‘strong.’

Wulfweard, the name of one of the heroes, means ‘Wolf Fate.’ Weard, wyrd or weird originally meant something like ‘fate’ or ‘destiny.’ The Norns, the Norse Fates, worked at a loom, ‘weaving our weirds.’ Although 'weird' is beginning to mean simply 'odd', it originally had nuances of eeriness, of supernatural intervention.

The villain of the piece is called ‘Unwin.’ ‘Win’ or ‘Wynne’ meant ‘friend.’ So the name ‘Unwin’ meant ‘un-friend’ or ‘not-friend.’ Or, put it another way, ‘enemy.’ I don’t know why anyone would want to name a new-born baby ‘Enemy’. Perhaps it was more than ordinarily prone to screaming all night and throwing up over people. Still, it seemed a good name for my hero's murderous half-brother.

‘Hunting’ and ‘Elfgift’ both meant exactly what they say: ‘one who hunts’ and ‘gift of the elves.’

Elfgift or Aelfgifu is only recorded as a woman’s name but that just means we have no surviving manuscript where it was written down in its masculine form. Anglo-Saxon names for men often begin with ‘Ael’ or ‘Al’. ‘Alfred’ and ‘Aelfric’, for instance. The Al or Ael meant ‘Elf.’ Alfred meant ‘Elf-Counsel’ and Aelfric meant ‘Elf-Ruler.’ The Elves were, perhaps, minor pagan gods— or at least, spirits of the locality, rather like the Greek dryads and naaids.

The hero, Elfgift, is supported and guided by a ‘battle-woman’ or Valkyrie named Jarnseaxa and her name is one of the ‘real’ Valkyrie names from Norse Myth. During the Saxon period there was a weapon sized somewhere between a broad-sword and a dagger, called a ‘seax’. It had a single edge and its name is thought to be derived from Old German for 'to cut'. ‘Jarnseaxa’ means ‘Iron Seax.’

|

| The remains of a seax and a replica -- wikimedia creative commons |

The ‘screamer’ on the cover of Elfgift declares, ‘I choose the slain,’ and Jarnseaxa several times repeats this. She's giving a job description. In Old Norse, ‘valkyrie’ means: Choosers of the Slain. The god, Woden, (Odin in Norse myth) sent His valkyries to find the bravest heroes on the battle-field. The Einherjar, or ‘ghost-warriors’, who often rode with the Valkyries, brought about the heroes’ death. They were then carried off to Odin’s Valhalla, or Hall of the Fallen.

|

| Torslunda helmet plate: Wikimedia: public domain |

[Left, one of the Torslunda helmet plates which is thought to show an Einherjar, or ghost-warrior, with a berserk who is wearing his 'bear shirt.' Which is what 'berserk' means.]

Odin knew that the Gods’ unavoidable doom (or weird) was to die in battle against the forces of Fire, Ice and Chaos at Ragnarok, the ‘Doom of the Gods.’ Despite knowing this Fate to be unavoidable, He was still determined to go down fighting. So He gathered a harvest of warriors, to form an army He would lead to battle at Ragnorok.

But Jarnseaxa, Elfgift’s ‘Lady’ is more than a mere elf, more even than a Valkyrie. She is the Goddess who was called ‘Freya’ in Norse myth, although ‘Freyja’, like the name of her twin brother, Frey, was a nickname. ‘Freyja’ means ‘Lady’ and ‘Frey’ means ‘Lord.’

Gods seem to be usually known by nicknames. Well, with all those mad followers, you can understand why They wouldn't want to reveal their true identities. ‘Woden’, for instance, means something like ‘The Raging One.’ (He gave alcohol to mankind.) He had many other names too: One-Eye, Wanderer, Grey-Beard, All-Father...

The Greek Gods were the same. Hermes, one of the oldest of them, was the god of travellers, among many other things. The roads that travellers followed were marked, at intervals, by stone cairns. A traveller, passing by, would maintain the way-marker by adding a stone to the cairn, while asking the god for protection from robbers, mad dogs and bad weather. Hermes’name, originally, seems to have meant something like ‘Old Stone Heap’ or ‘Heapie.’ Hermes would have liked the joke. One of his many, many jobs, by the way, was to be the god of 'all those who earn their living by words.'

| |||

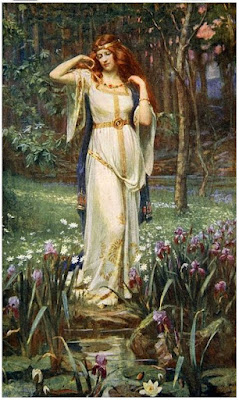

| Public domain: Freyja and the Necklace | | |

The Myths also say that Freyja shared half the dead from the battlefield with Odin (or Woden), which doesn’t fit too well with the cuddly, cooing ‘Goddess of Luuurve’ image. There are hints that, at some time in the past, She had much in common with the Valkyries. The other side of desire, love and birth is death and loss.

*

The school-children who read Elfgift were puzzled by another word:‘atheling.’

Several of the male characters are referred to as ‘athelings’.

‘Atheling’ was a title: it meant a prince of the royal house who was eligible for kingship. The Anglo-Saxons did not follow the principle that the king’s eldest son always inherited the throne. That was something that began after the Norman Conquest. (Quite a long time after, in fact. The first Plantagenets didn’t follow it.)

Instead the ‘aeldermen’ elected the next king from among the athelings, who might include the sons, brothers, nephews and perhaps even cousins of the last king. In theory, this meant that the best man could be chosen for the job from the available candidates and the problems caused by having a child or a fool (or a lying villain) on the throne could be avoided. (Though the antics of our present 'government' rather disproves that theory.)

So it happened that Aethelred (Noble Counsel), king of the Saxon kingdom of Wessex, was succeeded by his youngest brother, not his son. Which just goes to show that the aeldermen knew what they were doing, since the young brother became Alfred the Great.

The aeldermen were the ‘earls’ or ‘jarls’ who ruled smaller areas of a kingdom, under the king’s command. Jarl was pronounced ‘yarl’ and a slight shift in pronunciation gives you the English ‘Earl’: the only aristocratic title left that is derived from English rather than French.

|

| Wikipedia: The Silverdale Hoard |

Under Anglo-Saxon and Viking law everyone had a blood price: the price that you had to pay to their owner or relatives if you killed them. A valuable slave might be worth twelve ounces of silver. An atheling was worth— well, in fact, a lot more than twelve hundred ounces. But their blood-price had once, in the distant and legendary past, been reckoned as twelve-hundred ounces of silver and the phrase stuck even after inflation set in and the price of murdering an atheling just rocketed.

If you were one ‘of the twelve-hundred’ you could literally consider yourself worth more than others of lesser value. Or, your corpse was, anyway.

The theory was, that once a blood-price had been settled on and paid, all was forgiven and forgotten. In fact, as the Icelandic Sagas show us, the relatives of the murdered person were often not satisfied, no matter how high a blood-price was paid. They weren’t satisfied until they had murdered the murderer. The murderer’s relatives then demanded their blood-price— or took their own revenge. This could lead to a blood-feud which went on for decades.

But just imagine: six months of freezing darkness cooped up with the same people in a small house. No telly, no radio, no books...The only entertainment, going out into terrible cold to feed the few cattle in the sheds. Plotting bloody revenge at least gave you something to do.

The words ‘house-carl’ is used a lot in Elfgift too. What was one of them?

The Old Norse word karl and the Anglo-Saxon words ceorl or churl meant the same thing: a low-born man, a peasant, but not a slave. A low born free-man. (Our modern boy’s name Carl or Karl, is the same word.)

|

| Reconstruction of Godwinsson's banner |

The end of house-carls came fifty years later, in 1066. Harold Godwinsson, the last English king, was Danish on his mother's side. His house-carls went into battle with him, standing around him on the hill at Senlac, under Harald's banner of ‘The Fighting Man.’ They died under the banner, to the last man.

All those funny words and names...

Elfgift is now available at:

Comments

I expect we'll see Elfgift alongside Rosemary Sutcliff (if she's still popular) on the bookshelves.

I didn’t know we have Hermes to blame for the piles of stones that litter the sides of popular country paths. Yes I know cairns are meant to guide fellow walkers who come after you… but built at three yard intervals? Grrr.

Thanks for a terrific post.

One word that was new to me, and which I love, is 'dreich' for a grey, wet, cold, miserable day. I can't understand how such a great word got lost outside Scotland. It isn't as if we don't have dreich days in England!

And Griselda! I wish I'd known, while I was writing it, that 'gift' means 'poison' in German! Because Elfgift certainly has his poisonous side, like many pagan deities. But I must defend Hermes, who is probably my favourite god. So much more easy-going and sympathetic than the rest, less up Himself! He's only trying to make sure you don't get lost -- because it's His job to look after those who make their living by words.