A Glittering Gem of Black, Gothic Humour: Griselda Heppel is intrigued by O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker

Recently a friend brought a book for me to read. It had achieved the extraordinary feat of being enjoyed by every member of her rather scary book club, so naturally I was intrigued.

Having a way of thought that jars with others' lies at the root of her unhappiness; but it also means she sees what they don’t. As a small child, passing Institution Row where the war-wounded live fills her with terror:

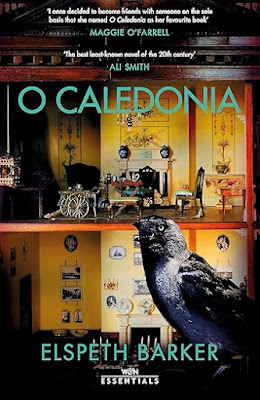

The book was O Caledonia, by Elspeth Barker.

Set in a bleak, harsh landscape of 1920s Scotland, it is a glittering gem of black, gothic humour, the like of which I have never come across before. All the rules of story creation are thrown out the window. The heroine, Janet, is an unlikeable, awkward, bookish girl who relates to animals better than to people, and whose selfish instincts make her difficult for the reader to sympathise with. Moreover, she’s killed off on page 1. Found, at the tender age of 16, clad in a black lace evening dress, stabbed to death at the foot of Auchnassaugh Castle’s great stone staircase. Not what you’re meant to do as a writer because, well, why would anyone read on if the main character is already dead? What kind of mind writes a coming-of-age novel in which the coming-of-age never happens?

|

| O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker |

A sharp, perceptive, utterly original mind, fizzingly alive to the dark comedy inherent in the human condition and in our abject failure to understand each other, that’s what. Janet’s difficult character contrasts with the softer, kinder natures of her younger sisters; she is constantly being berated for her selfishness by her parents and she is friendless at school. But it’s clear to the reader that she doesn’t mean to be like this; she simply can’t help the way her mind works. Told, age 6 or so, to bring her baby sister in from the garden, she drags the child by her head out of the pram and across the grass (the fact that little Rhona sustains no serious injury certainly strains one’s suspension of disbelief at this point). No ill motive on Janet’s part; she just takes the instruction too literally.

|

| British wounded at Bernafay Wood, 19.07.1916 Ernest Brooks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Having a way of thought that jars with others' lies at the root of her unhappiness; but it also means she sees what they don’t. As a small child, passing Institution Row where the war-wounded live fills her with terror:

Some were crazed from shell shock and nodded and muttered to themselves, others displayed the magenta stumps of amputated arms and legs.

Yet at a children’s Christmas party in the village hall, she is the only person to approach the disabled men, sitting at the back, and engage with them as people, addressing their wounds directly:

'Please may I touch your arm?’ she asked. The man stared at her, still smiling. Her knees were shaking but she stretched her fingers up and gently she stroked his puckered stump; it was like paper, dry and smooth, even where the violent scar lines twisted and rippled…

It’s a moment of touching humanity, of solidarity between different kinds of damaged people. Which is why, when looking online for reviews of this extraordinary book, I was puzzled to come across an article entitled 'Ableism in O Caledonia', which accuses the book of depicting ‘disabled people, particularly men with obvious, physical disabilities, as horrifying and violent. The novel never dispels this ableist impression.’ The author, Grace Lepointe, cites the above scene as proof, whereas what struck me was the pathos of these injured veterans, and their delight in normal communication within a society that treats them with pity while shunning them as pariahs.

Significantly, the wounded man connects with Janet (who has always hated her name) on a level that fills her with joy:

‘You’re a braw wee lassie,’ he said. ‘what’s your name?’ ‘Janet.’ ‘That’s no name for you. I’ll call you Beth.’ Beth. A beautiful name, a velvet name, brownish mauve.

Barker is writing through a child’s eyes. Children don’t follow rules about what they ought to feel; they can only respond with fear, alarm, curiosity and, hopefully, relief to new situations they find scary. Barker shows this clearly, but Lepointe is disappointed. ‘I hoped that this long passage would lead to Janet eventually realizing she was wrong about the veterans and no longer fearing them.’ Yet this is exactly what this passage does do. Janet progresses from terror to curiosity to confidence to warmth, even gratitude towards the man. Short of writing a tedious, artificial and totally unbelievable interior monologue for Janet in which she spells this out for herself, I’m not sure how Barker could have done it better.

Anyway, read O Caledonia, if you haven’t already. It is beautifully written, evoking a spartan, gloriously eccentric Scottish upbringing, with a spiky, clumsy, clever, lonely heroine fighting her corner in a world that doesn’t understand her.

Comments

This is a new word and concept to me but I met an instance of it recently in a book by Evelyn Waugh which I had recommended to a book group. As I was re-reading Decline and Fall I was horrified to discover humour about poor mental health. There was also a lot of racism in the book too which I had forgotten about completely.

I suppose there is a lot of difference in what I read in the 60s-70s and now and our attitudes have really changed. Perhaps your blog will open up the column to discussion of the various isms that we might find nowadays in our cultural studies.

You are quite right about how assumptions have changed about what is acceptable to laugh at, and a good thing too. Hardly surprising really... I just checked when Decline and Fall was published and it was nearly 100 years ago! My defence of the scene with the WW1 veterans in O Caledonia is coloured by the fact that I've read about many of the wounded after WW1 feeling invisible - people wanted to forget the horrors of the war and that extended to excluding anyone whose tragic injuries reminded them of it. Awful further punishment for these poor men. Hence Barker's including them in Janet's life experiences felt a positive thing.

Funny thing, this humour business. A few years ago I was aghast at a performance of the very popular One Man Two Guvnors at the NT, in which the entire comedy of a scene hinged on an elderly waiter repeatedly being hurled downstairs, smashed against a door etc. The audience roared with laughter. I couldn't find it funny. Of course the actor wasn't hurt (I hope), he was a professional, but I was staggered that it was felt OK to laugh at a vulnerable character being mistreated that way. Seems ageism is still fine when other prejudices are not.