Violent Femmes | Karen Kao

|

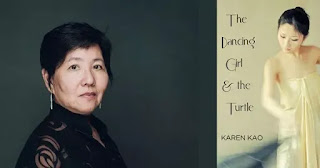

| Poster for my master class for the International Writers' Collective |

Last summer, I gave a master class in novel writing for the International Writers’ Collective. Or rather, I squirmed in the hot seat while director Sarah Carriger peppered me with a series of home questions about my novel The Dancing Girl and the Turtle.

I did my best to answer her as well as the lively crowd that kept lobbing new ones at me. There’s so much more to say in response to all those questions but here I want to zoom in on two aspects of that class: the use of violence and historical fact in fiction.

silence

The inciting incident of my novel is the rape of Song Anyi. The event is horrible in every possible way but, to my mind, the real violation comes later. The Dancing Girl and the Turtle is set in Shanghai 1937. The city is a no-holds-barred kind of place where everything and everyone is available for sale at the right price. In that market, Anyi would be damaged goods if her rape were to become common knowledge. Denied the right to speak of what has happened to her, Anyi turns inward to self-harm.

There is a lot of violence in my novel and Anyi is at the receiving end of much of it. Those scenes however are relatively brief and the tone consistently neutral. I tried to avoid waxing poetic or commenting on the tragedy of the situation.

Those were all deliberate choices. But when Sarah asked during the master class, why I chose to voice Anyi in first person, I had no good answer. I had never thought about Anyi’s story in any other form. But as sheer dumb luck would have it, there is an excellent craft reason for opting for letting the victim speak.

authenticity

Rene Denfield is a crime fiction writer, a licensed investigator and the victim of child abuse. Having witnessed the real thing, Denfield rails against the use of violence and violation as a mere plot device.

Unfortunately, much writing about violence is itself a violation. Violence—especially rape—is often used as a trope. The character is only there, on the page, to be torn apart. It’s not an accident that most literary victims are women of color, prostitutes, and the poor. Such victims are splattered across the page without any regard to their suffering. The character is denied both dignity and the autonomy to interpret their experience outside an expected range of reactions that include: shattered forever, destroyed, defiled. Violations are presented in detail, and yet the point of view often reinforces the offender, so that even while being raped on the page the victim is denied voice.Denfield isn’t arguing against violence in fiction. She wants more of us to tell the truth about violence against women, the poor, the outsiders who continue to be violated because no one else cares.

To start with, we must imagine our characters as real people. We must honor the victims by telling their truth with an effort at genuine understanding, not just of their experiences but of the world in which they live. We must focus less on the details, more on the feelings. A single humane sentence can tell a far deeper truth than any catalogue of depredation. We must give voice to the victims.

down the rabbit hole

But wait a minute. Denfield says to focus less on the details. Isn’t that contrary to what we discussed in the master class as well as every other class at the International Writers’ Collective? Details are the way an author grounds a story in a time and place. Details can contribute toward the development of mood and character, too.

Dead leaves fill my mouth, strangely sweet.That’s the last thing Anyi notices before the rape commences. It could just as easily have been the snap of a buckle or the smell of betel nuts on the man’s breath. I think that Denfield is saying the same thing you’ll hear in class: choose your details carefully. Not only do you want a detail that only the victim can observe, but one that is uniquely personal to her.

Easier said than done.

One of the most difficult things for a novelist to do is choose. Take the problem of the overpopulated novel. You’ve designed each character to serve a particular purpose but now there are so many, it’s become the cast of thousands. Who do you kill? Rebecca Makkai has come up with the clever idea of character folding

Folded carefully together like egg whites and cake batter. […] And suddenly I had, instead of three characters each serving one function, one character with complexities and contradictions and nuance. I had a human being more three-dimensional than any of my original characters had been.

chaos theory

When it comes to writing historical fiction, the problem of choice increases exponentially. You do all your research. You learn so many cool historical facts. It’s imperative to use them all! But there’s another, much bigger problem lurking behind historical fiction.

Chance led Nick Dybek to a single detail that launched him into writing a novel about WWI. But before Dybek would commit a single word to the page, he wanted to get his facts right. Off he went, down the rabbit hole, to read every book ever written about WWI.

There was something of an addict’s logic to the process: just one more book and I’ll know enough, just one more and this will be easy.Dybek proceeded to stuff himself full of historical arcana and then he turned around and did the same to his manuscript. He put in everything he knew, afraid to leave a single fact untold. The result was underwhelming. Dybek’s conclusion was:

there is such a thing as too much research. Too many facts can squeeze the breath out of a text, yielding a fictional world that feels authorial, unnatural. And, if one of the goals of writing a novel is to produce a narrative that feels life-like, and, if life-like means as surprising as an Archduke’s assassination, as random as years of research occasioned by a twist of the radio dial—then perhaps the writing process must embrace that chance, that chaos.

in class

I like chaos. I write without a plan and with little to no research under my belt. My fear is that I’ll spend all my mojo collecting facts or trying to reconstruct history when, for me, it’s the story that matters. No plotting, no planning, just flying by the seat of my pants.

The hope is that I’ll surprise myself. Stumble upon the metaphor or passage or through-line that illuminates the rest of the way. Like obscenity, I can’t define it. I’ll know it when I see it. A world that feels real with characters made of flesh and blood whose actions make sense within the logic of their lives.

But then the chaos gets into my brain. I know there’s something wrong with my manuscript but I don’t know what. That’s when it can be useful to join a master class, a workshop or a writing group. I say can because you also need to be in the headspace to hear that feedback and put it in its proper context. After all, you’re the author. It’s your manuscript. You decide whether to alter it at all and, if so, how.

For me, a master class isn’t about delivering factoids. It’s for sharing stories and fears. To signpost some of the very many roads that can lead to publishing success. At its very best, a master class should inspire. At least, I sure hope so.

Notes:

- For authors looking for examples of violence in fiction, check out: Bastard out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison, Winter's Bone by Daniel Woodrell, The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan and all the works of Yoko Ogawa.

- If you're up for a nice tune and a cool clip, check out this video of the Violent Femmes.

- "Violent Femmes" was first published by Karen Kao on her blog Shanghai Noir.

Comments

Agree with everything you say about writing about violence too.