Nick Green: Publish and be dimmed

|

| Me under the floorboards |

There’s a typescript of a novel under the floorboards of my

house. Some months after we moved into the place, we mustered the willpower to

rip out the hideous brown carpet downstairs and put down laminate flooring, as

befits every stiflingly middle-class existence. When I say ‘rip out’ I mean of

course ‘pick up the phone and call the flooring people’, and when I say ‘put

down’ I mean put down the phone. But I was very much in the house. I saw it

happen.

Because I was there, on the front line so to speak, I was

able to see the ‘real’ floor of the living room when the carpet came up. Almost

in the threshold of the living room (this is important, treasure-seekers) were

a few loose boards. I defy anyone confronted with a few loose floorboards not

to prise them up and peer down into the void. (Aside: I’ve also noticed that,

whenever you strip wallpaper from a wall, there is always writing underneath,

graffiti, drawings, bizarre demonic messages, etc. Always.)

Under my living room floor was a dark, cool space above a

bed of gravel and assorted detritus, left presumably by the builders of the

house, many moons ago. It was dry and airy under there, and it occurred to me

that something sealed in that space might survive unchanged for many more moons

to come.

|

| But this one is quite good. |

Upstairs I had a complete typescript of my first ever

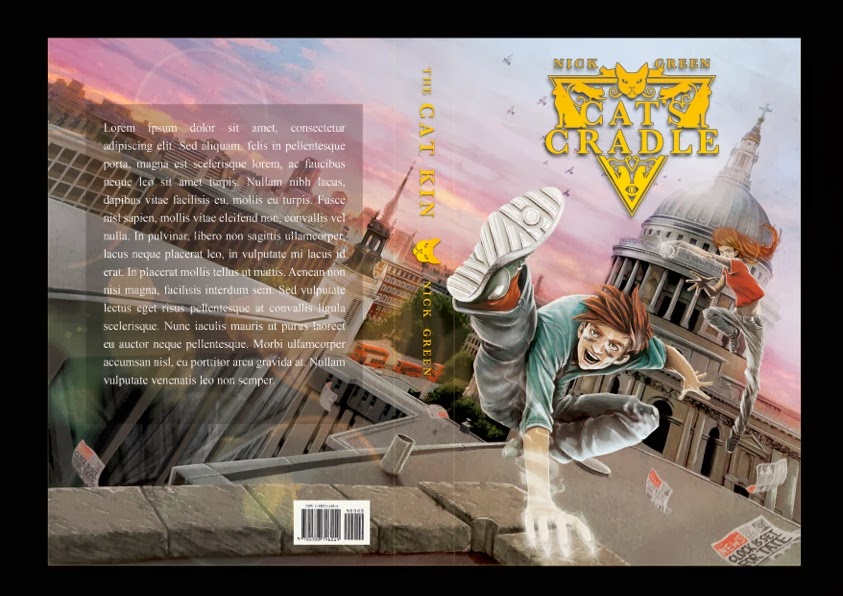

children’s novel. (This wasn’t The Cat Kin – that was just my first published novel. This story was called

The Century Spies and – by coincidence – it was a story about children finding

a long-buried time capsule containing letters from the past. I think you can see where this is heading by now.)

For two years I had been trying and failing to get agents and publishers

interested in this magnum opus. Some liked it, but all agreed it was ‘missing

something’. No-one could quite tell me what. So I had the tatty

typescript still kicking around the house like a teenager who refuses to

acknowledge that he’s now of working age.

There I stood, staring into this hole in the floor beneath

my house. I fetched the typescript from upstairs, wrapped it in plastic bags

and slipped it down into that hidden space. A few hours later, the laminate

floor had been laid, leaving no sign that anything might be hidden beneath.

I like to think that one day, in the far future, maybe not

till the house itself is demolished, someone (or some hyper-evolved woodlouse)

may come across that wrapped package, and they will open it, and they will

discover the last surviving copy of ‘The Century Spies’. And they will

find out what a bad writer I was.

Because all those agents and publishers? They were right.

Every single rejection letter they sent me was justified. The story sucked.

Individual passages might have seemed well-written, but taken together they

didn’t amount to a hill of partially digested beans. Because it wasn’t a book.

It was practice.

Now I breathe a sigh of relief that e-publishing wasn’t

around in those days. If it had been, then ‘The Century Spies’ would be out

there now. As would, no doubt, my previous ‘novels’ (oh! Didn’t I mention

those? They were sword-and-sorcery. ‘The Century Spies’ was Tolstoy compared to

those). All my excruciating juvenilia would be loose in the world, to haunt me

for ever more.

|

| And this one is a bit better |

‘It is better to remain silent and be thought a fool, than

to speak out and remove all doubt,’ said Mark Twain or Abraham Lincoln (except

that it was probably neither of them – they took it so literally that they

didn’t even say it). And sometimes, it’s better to remain unpublished than to

push your work out there before you’re match-fit. When you publish a book,

you’re effectively saying, ‘This is the best I can do.’ And then you go on to

believe that.

But it cuts both ways, too. When an editor rejects your

book, they aren’t necessarily saying, ‘You aren’t good enough.’ They might be

saying, ‘I believe you can do so much better than this.’

|

| And I did. |

Comments