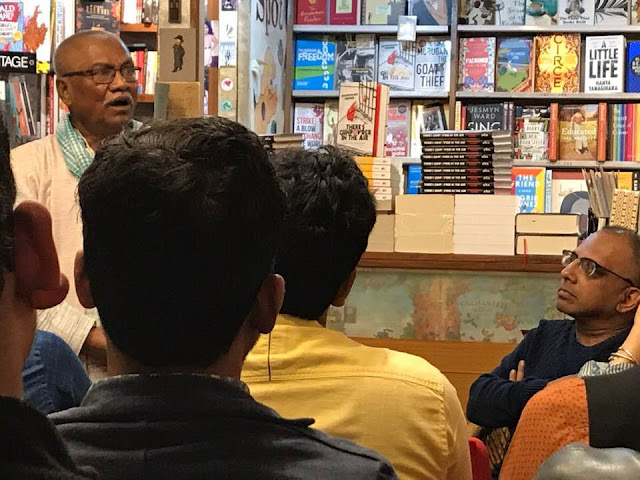

No Appropriation Here: Dipika Mukherjee meets Manoranjan Byapari

On February 24, 2019, Manoranjan Byapari was

launching a new book, titled There's Gunpowder in the Air, translated by Arunava Sinha. I was lucky to be in Delhi, and meet him.

As an Indian writer, I feel privileged to be alive and writing at a time when so many regional voices from India are available in translation. As a postgraduate scholar in Texas, it had irritated me to see upper-class Indians with the privilege of their elite English educations building an academic reputation on whether subalterns could speak; clearly, in these cases, the people being spoken for would never read the lofty ivy league theories being spun on their behalf.

So it is a pleasure to hear someone like Byapari, a Dalit who taught himself how to read

while in jail, speaking for his people while deconstructing his own life. And what a raconteur he is! Having

worked as a rickshaw-puller after being jailed for his political views, he spins tales of rage and redemption from life, and has gone on to win many literary awards, including the Hindu Prize for

non-fiction in 2019.

In India, English speakers are still the elite, and the language wields considerable economic power in a country

always attuned to global migration and trade. Yet it is within the regional languages

that the majority of Indian people lead their daily lives, both transactional

and social. Byapari, and other writers of his ilk, are giving a validity to

the much-maligned vernacular languages. In this post (translated by Arunava Sinha), Byapari writes:

What I said was completely different. It is not as though I have to fall in with someone's views just because they are a celebrity amongst Dalits. I do not acknowledge any such compulsion. I felt what he was saying was incorrect, and so I opposed his viewpoint.

I

always emphasise that there is caste within class, and also class within caste.

What I have learnt from my own reading and understanding is that, ever since

the time of B R Ambedkar, those who have led the agitations highlighting the

problems of the Dalit community belonged to its upper reaches…

Those

who are Dalits as well as poor face six specific problems: food, clothing,

education, houses, healthcare, and social respect. For the leaders of the Dalit

community, the first five problems have been solved in one way or another. What

remains is just respect. This is the only issue on which they speak from

different platforms and write in the media. What they're trying to say is: we

have become well-educated and cultured gentlemen, so it's time for upper-class

society to acknowledge us as equals and accept us in their social circles. This

is all they need for their discontent and their rage to die down.

But

the ordinary Dalit does not seek such respect. It doesn't even occur to him.

I've seen that when a 'gentleman' addresses a rickshaw-driver old enough to be

his father in the most humiliating way, and then offers an extra rupee or two

as the fare, the same rickshaw-driver is overwhelmed with gratitude. For he can

use that money to buy a little more rice. Starvation is agonising, and this

will bring him a little relief.

I

am reminded of an incident from a long time ago. It was during the Durga Puja

celebrations. A member of the Dalit community used to deliver water to

different shops. One of his regular customers ran a biriyani store, a shop with

a formidable reputation, which ensured that its owner never served stale food.

On that particular day some of the biriyani had remained unsold. The next morning,

spotting the water-supplier, the shopkeeper shouted – I have about four plates

of biriyani from yesterday, come and take it. Courteously the water-supplier

replied – Dada, let me just deliver the water to that shop there, I'll collect

it right afterwards. The shopkeeper said – I've waited a long time for you, the

pots and pans have to be cleaned. Take it right now or I'll feed it to the

dogs.

The water-supplier's face fell. He went up to the shop and packed the stale biriyani, garnished with humiliation, in his gamchha. He didn't mind, but I felt myself smarting under the shopkeeper's assault. Calling the water-supplier, I told him – You're no better than a dog. He'll give it to a dog if you don't take it. How could you accept that biriyani from him after this? Distressed, he said – Dada, you think I don't know he was humiliating me? But how does it help to know this? I haven't been able to give my children a treat for Durga Puja. Can you imagine how happy they'll be when I take this biriyani home? It was this thought that made me swallow his insult.

This then is the life of the Dalit poor. Helpless, powerless, and humiliated. I have risen from this class of people to talk about them. These are people who have no time to think about respect or status, for they're perpetually stricken by thoughts of how to extricate themselves from starvation. These people, my people, cannot even give their children enough to eat—how will they send them to school? Instead they send them to do the dishes at roadside restaurants, to work as servants at gentlemen's homes.

Even

if they do manage to send them to school, none of the children make it as far

as high school. Their education stops at Class Four or Five. How are they going

to study in English? If they are put under pressure to learn a foreign language

in primary school, they will neither master that language nor become proficient

in their mother tongue. It will be far more useful for them to at least learn

their own language properly.

And so I opposed Kancha Ilaiah. I said, let those who have the power to do it learn English, or even Hebrew for that matter. But there is no need to impose the language on ordinary people.

English

is the language of the gentlemen's class, it is the language of power. Wherever

I go, I see that those who can speak English fluently are held in great esteem.

I am aware that becoming experts in English will deepen the respect that Dalit

gentlemen command, it will widen their circle of power.

But

I will be able to consider fighting for the right to use this language only

after I have released the class of people for whom I speak up from their first

five problems. That is the war we must win first. Food and clothing. All else

can come later.

The success of Dalit writers like Byapari opens up a dialogue for the unfiltered

speech of those who have not had a voice for so long. In New Delhi, where the

majority of the audience did not speak Bengali -- the language that Byapari

writes in-- he spoke eloquently in Hindi to a young crowd that bantered with

him, although they were there to buy his book in English. It felt like the beginning of a multilingual utopia with multiple languages jostling

in amity, rather than hostility. It felt like the beginning of some necessary, and long awaited.

Comments

I can relate to the history and tyranny of linquistic strata in my own oblique way, having witnessed this in the Italian American and Italian cultures while growing up.Back when Italian Americans could still be considered a relatively disadvantaged minority in the 1940s and even 50s, the affluent and influential from the old country spoke and wrote proper Italian, as opposed to impoverished working-class migrants to America, many of whom spoke only their mostly southern dialects, eg. Sicilian, Neopolitan... almost distinct languages. Many were functionally illiterate, having grown up before universal education in Italy... At the same time, some of Italy's greatest writers, have been from Sicilly, (eg. Luigi Pirandello, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa) fluent in dialects and Italian - an offshoot of Tuscan, which itself became the Italian national language, in part because Dante chose to write his Divine Comedy in his vernacular Tuscan, not Latin, as was proper back in the 13th century.

It's so true, as you write that "there is caste within class, and also class within caste."