A Popish Plot in Twickenham Contains a Popish Grotto, Finds Griselda Heppel

|

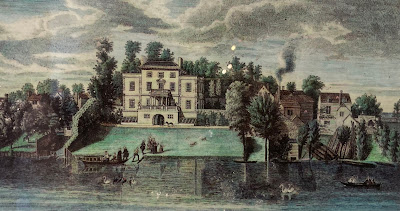

| Radnor House School, Twickenham |

It’s quirks of architecture that appeal to me. When a school is made up of a jumble of old buildings, all from different historical periods, the scope for hidden doors, secret rooms and passage ways is extremely appealing (as you might tell from the way these elements crop up in my books, taking my poor heroes on terrifying journeys). Until a week ago, I thought I knew the limits you could go to with a school’s environment without losing all sense of realism and thereby your readers’ suspension of disbelief; but then a week ago I’d never heard of Radnor House School.

|

| Alexander Pope's villa. Engraving by Nathanial Parr from 1735 painting by Michael Rysbrack |

Radnor House is an attractive 19th century red brick building in Twickenham, west London, with a glorious frontage on the Thames and its own grotto underneath.

Yes, you read that right. Its own grotto. And not just any grotto. (Is there such a thing as Just Any Grotto? Discuss.) This one dates back to 1729, when a fine Palladian villa belonging to the great poet Alexander Pope stood on this spot. Between translating the works of Homer and sending up contemporary mores in The Dunciad and The Rape of the Lock, Pope took great interest in gardens and garden design. One problem: his five acres of land lay on the other side of Deep Cross Road from his house.

|

| Plan of Pope's grotto (Pope's Grotto Preservation Trust) |

Centuries passed. Pope’s villa was torn down and other buildings erected in its stead. But the grotto remained, and in recent years the Pope’s Grotto Preservation Trust was set up to restore it. Work has begun but there’s still more to do, which is why the grotto can only, for the time being, be viewed on special Open Days. A friend alerted us to the most recent one and my husband and I leapt at the chance.

|

| Looking down the central chamber to the tunnel in Pope's grotto |

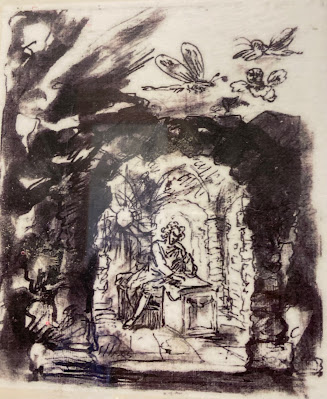

With the aid of a wonderfully informative volunteer, we explored all the fascinating details. Captivated by geology, Pope decorated the walls, not with shells, as became fashionable in the 18th century, but with stones and minerals, fossilised sponges and pieces of petrified wood. There are even two basalt hexagons from the Giant’s Causeway. He cleverly inserted three mirrors at angles to reflect light from the river (now sadly blocked by a school building), making the minerals on the uneven surface of the walls sparkle. The effect was enhanced even further by the suspension of – wait for it – an alabaster ball from the ceiling that glittered as it revolved in the breeze, as shown in William Kent’s drawing of Pope in his grotto.

|

| Alexander Pope in his Grotto by William Kent, 1725-30 (Chatsworth Settlement Trustees) Note the disco ball to the left of the poet's head. |

Whaaaaaat? On top of writing some of the most famous poems ever written, coining aphorisms, designing gardens and pursuing geological interests, Alexander Pope invented the…. disco ball? Was there anything the man couldn’t do?

Looking at Kent’s drawing, I did wonder. Given the cold, the draughtiness, the gloom – even if relieved by scattered gleams of light – and the general lack of comfort, could Pope really have sat at his desk in the middle of the passage and written reams of poetry? The privacy and lack of distraction would be a great plus, certainly.

But for a man who could build his own Palladian villa, there must have been easier ways of finding those.

Comments

I have made amends, however, and my small poetry group recently had a session on Pope at which I was able to display my literary knowledge of him. If I'd had your post earlier, I would have been able to say a lot more. So I'm making a note of The Grotto Preservation Trust which sounds fascinating.

Thanks for an informative blog

I did enjoy The Rape of the Lock though.