When Not to Self-Publish by Lev Butts

It's no great secret that it is not easy to get published traditionally nowadays. Not that it ever was a walk in the park, but it seems the writing market is particularly glutted today. In fact, as a writer starting out, if you can't show that your work appeals to pretty much everyone on the planet, the chances of seeing your book on the shelves of Barnes & Noble are pretty slim.

For starters, most commercial publishers require that you have an agent to represent you. Most agents require that you have been published before taking you on. This is why so many writers are alcoholics.

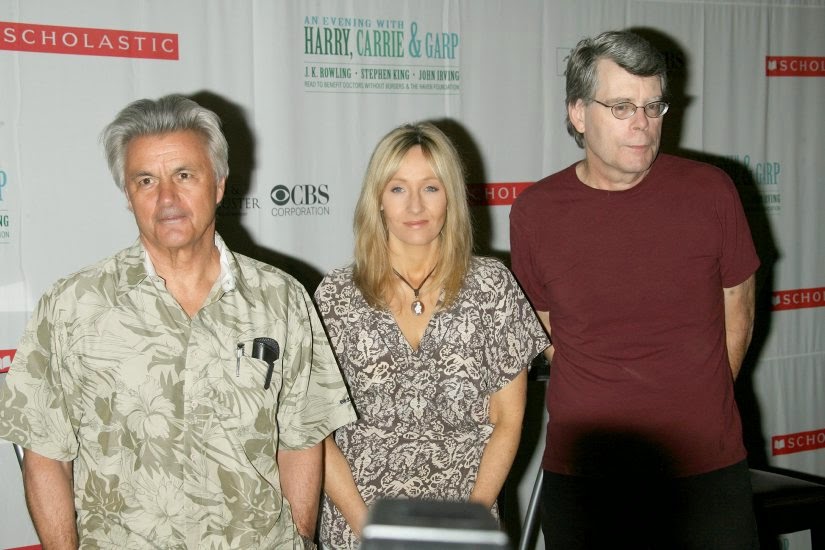

Of course it helps if you know people in the publishing industry and are not too proud to ask for a favor, but last I checked, Stephen King, J. K. Rowling, and John Irving are all full-up on friends.

|

| Pictured: John Irving, J.K. Rowling, Stephen King, and No Room For Me |

Last week, I received my first rejection from a "real" publisher, and this wasn't even for a work of fiction. It was for the first critical edition of H.P. Lovecraft's work. It would have included six of his most famous stories, two of his poems, and an abrdged version of his essay, Supernatural Horror in Literature. It would also have included new and reprinted essays on Lovecraft as well as reflections by other horror/sci-fi/fantasy writers on how Lovecraft influenced their own writing.

In other news, I have recently given a friend a copy of Emily's Stitches to show his agent later this week. When I told some of my independent publishing students about this, several seemed taken aback that I would "sell out" like that. Similarly, others wondered why I didn't just take my Lovecraft manuscript and self-publish it.

Here's the thing: Publishing is not an either/or proposition. There is nothing wrong with self-publishing, nor is there anything amiss with traditional publishing. Essentially, publishing is simply the logical step in any artistic endeavor. If you paint or sculpt, it seems only natural that you show your work to people either by through a gallery or through your own efforts. If you are a musician, it is perfectly understandable that you would press a CD of your music and make it available for purchase. Obviously, it's nice if a major record label picks you up, but no one thinks twice if you simply put the money up yourself and release it independently.

Publishing your book is exactly the same thing. Why wouldn't you publish something that you have worked so long on? Before I published Emily's Stitches, most of those pieces had been sitting useless on my hard drive for years. It seems absolutely ludicrous that I would have written those stories and just let them sit unused for over a decade. Self-publishing them meant that at least a handful of other people got to share the stories and appreciate them.

And there is absolutely nothing wrong with that.

I'm sure E. L. James would have been perfectly happy if her books had remained fairly successful self-published works.

|

| I know I would have been. |

However I don't (much) begrudge her success in getting them traditionally published and becoming a best-selling author. I certainly don't think she "sold out."

I know writers who both self-publish and traditionally publish. The friend who is showing Emily's Stitches to his agent, for example, is a best-selling writer of children's books, but he also is fairly successful at self-publishing hard-boiled detective stories, making about $800-$1,000 a month in sales on Amazon.

My reasons for self-publishing are made up of equal parts laziness and practicality. I simply don't want to devote the time it would take to shop my work around, knowing the chances of success are slim and the chances of making any real money if accepted are slimmer; I'd much rather spend that time writing or working on my actual job of teaching. Similarly, if sharing my work is my ultimate goal when I write, it makes practical sense to self-publish given the quick turnaround in getting my work on a cyber-shelf (ebooks can be available for purchase usually well within 24 hours of submitting them) and the minimal amount of money it costs me to do so (usually the cost of purchasing a proof copy).

So why not publish my Lovecraft book myself? There are several reasons:

It Would Cost Me Too Much Money

While I can publish my own work independently at little or no cost to myself, publishing someone else's work is a different matter entirely. Contrary to popular belief, much of Lovecraft's work is still under copyright, meaning I would have to pay the Lovecraft estate for permission to use the material. Even if each selection cost me $100, self-publishing almost guarantees that I will not make that money back. I might as well throw it out into space.

|

| H.P. Lovecraft's lesser known tale, "The Colour of Money Out In Space" |

It Will Do Me No Good To Do So

I write fiction because I have a story inside me (often several) that need to get out. I get ideas, and if I don't write them down, they just go away leaving me with kind of an empty feeling. Even the bad ideas need to be written down before I abandon them as bad ideas, but the good ones especially need to be put to paper.

Once I've done so and decided the stories really were worth the time and effort, it seems only natural to share them with others who might enjoy them. So off to Lulu or Createspace I go, and within a day, I can let my followers know the book is up and ready for purchase.

The Lovecraft book is different, though. While it does have fiction in it, it's primary purpose is as an academic work. I write academically primarily to get promotions at work. This means the works have to be published by "reputable" publishers. I am NOT a reputable publisher; in fact as a publisher, I literally have no reputation at all. Self-publishing the book, then, would not do anything towards my primary goal of earning a promotion and getting to buy more food and pay off more student loans.

Another reason I publish academically is to share my ideas with other academics. Even if the book were published traditionally, only a handful of academics would be interested enough in the book to read it. Self-publishing it, and the much more limited promotional resources that implies, would effectively lower that number of academic readers to something roughly resembling zero. Similarly, as a critical edition, the book would primarily be used as a college-level textbook. Self-publishing means professors literally have no way of knowing about my book and can thus not assign it for their classes.

|

| To the left the audience for the Lovecraft book if published traditionally To the right: the audience of the Lovecraft book if self-published |

I Would Have Nothing To Publish

I have been fortunate in finding contributors for this book, especially given that it is a book that had no publisher contract when I began working on it. Several authors graciously agreed to contribute memoirs for free. Two major Lovecraft scholars, S.T. Joshi and Robert M. Price, also donated essays gratis. Other scholars submitted essays under the impression that it would be a scholarly/academic publication and thus add a line to their curriculum vitae and give them a publishing credit towards tenure and promotion.

Self-publishing would mean their work would do them little good, given that I am not a traditional publisher and my audience would be incredibly limited. They would almost certainly ask that their contributions be returned so that they could use them in other, more academic venues. I would be left, then, with a very short collection of Lovecraft's work that would cost the consumer (given the costs discussed above) about three times what it would cost them to purchase a collection of all Lovecraft's work from their local bookstore, even if they special ordered it from Yuggoth.

|

| Behold! My self-published critical edition of H.P. Lovecraft! All for the low low price of $100! |

I spend a lot of time discussing, both here and elsewhere, when one should self-publish a book. So much so that one might think that I am in favor of always self-publishing.

I am not.

Self-publishing is a viable avenue for most works, but it is only one avenue of several. Before making the decision, one should always consider who the intended audience of the work should be, how much money a project will cost, and whether self-publishing will reach that audience and cover those costs.

If the answer is no, then you should really consider other routes.

As for the Lovecraft book, I intend to revise it, and try another academic press.

Comments