Singalong with the Sterkarms by Susan Price

|

| A Sterkarm Tryst by Susan Price |

Tryst: (Old French) an appointed station in hunting. An appointed meeting place, often of lovers. To engage to meet a person or persons. A cattle market, e.g. 'The Falkirk Tryst.'

A Sterkarm Tryst: an appointed meeting place of which only one side is aware: an ambush.

Yesterday, January 24th, the third Sterkarm book, A Sterkarm Tryst, was published.

It's the third in the series. The first two, after being out of print for some years, have been republished by Open Road. They are The Sterkarm Handshake and A Sterkarm Kiss.

It's the third in the series. The first two, after being out of print for some years, have been republished by Open Road. They are The Sterkarm Handshake and A Sterkarm Kiss.

|

| The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price |

|

| A Sterkarm Kiss by Susan Price |

(I've just been messaged on Facebook by a reader, who tells me she can now at last read Kiss, which she's been trying to find for ten years, and has pre-ordered Tryst. I can only say thank you for your stamina and thank you again.)

The books were inspired by the reivers of the Scottish Borders though Handshake only came to life for me when I thought of sending workers for a 21st Century company through a time machine to the 16th Century Border Country, where they hope to mine the coal, oil and gas. The 16th Century 'natives,' the Sterkarms, suppose them to be Elves. After all, the strange clothes of the 21st Century people give them an eldritch appearance and their carts which move without horses demonstrate their supernatural powers.

The Sterkarms, the local Riding or Raiding* Family, welcome the Elves at first, for their magical wee white pills which take away pain (aspirin). The welcome doesn't last. The Border men were notoriously 'ill to tame,' as a contemporary put it, and the Sterkarms don't relish being told what they can and cannot do, even by Elves.

*The word 'raid' is from the Scandinavian or Scottish form of the Old English 'rade', which meant 'road.' Our word 'road' is from the same Old English word, which also gave us 'ridan' or 'ride'. A road was where you rode. A track over a moor or through a wood is still called 'a ride.'

Raiding was often what you were doing when you rode down a road or ride. So a 'Riding Family' and a 'Raiding Family' were the same thing. Ride, road and raid all stem from the same word.

And 'reivers', as in Scottish Border reivers, comes from the same root as 'bereave,' which survives to the present almost exclusively in the sense of bereavement by death. 'To reave' originally meant to rob, to take, to forcibly deprive.Looking back over the books, I realise that the words and music of old ballads run through all of them. (I hear the music, anyway.) The 21st-Century heroine, Andrea, is 'embedded' (in more ways than one) with the 16th-Century Sterkarms and learns many songs from them. She finds that the songs often give her the words to understand the Sterkarms and her own situation.

I just thought you might like to know that.

The higher on the wing it climbs

The sweeter sings the lark,

And the sweeter that a young man speaks

The falser is his heart.

He'll kiss thee and embrace thee

Until he has thee won,

Then he'll turn him round and leave thee

All for some other one.

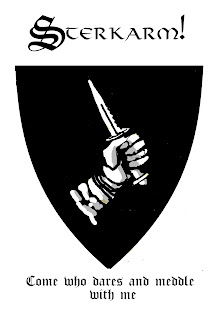

Then there's the ballad which gives the Sterkarms their rallying cry and boast:

My sword hangs down at my knee,

I never held back from a fight:

Come who dares and meddle with me!

A 'hob' was the breed of small, strong, intelligent horse which the reivers rode (down roads on raids). This ballad was historically associated with the Elliot family rather than the Armstrongs on whom the Sterkarms are very, very loosely based. ('Sterkarm' means 'strong arm.)

These old songs fitted themselves naturally into the story as I wrote. I'd known many of them by heart for decades before I had any idea of writing the Sterkarm books. I never had to hunt for a quote. The scene I was working on would set a particular song playing in my head.

I knew the songs because, while still a young teenager, my love of folklore led me to Child's Ballads. I was already familiar with the lyrics before I discovered recordings of them by various folk-groups and singers.

I was a deep-dyed folkie, me. I was having none of your long-haired sensitive types strumming acoustic guitars while they intoned modern protest songs. If it wasn't at least 200 years old, I didn't want to hear it. I wanted elbow-pipes, Shetland fiddles and bodhrans. I wanted people with closed eyes singing unaccompanied with one hand over an ear. "As I walked out one midsummer morning..."

It was the stories, of course, that attracted me. I wanted to hear about the Billy Blind starting up at the bed's foot and the loathly worm toddling about the tree. And the Broomfield Hill. And Twa Corbies.

I often listen to music while writing and, for me, the music has to be fitted to the book I'm working on. It creates the atmosphere. For the Sterkarms, it had to be traditional folk, especially the Border Ballads. The music and words of the ballads were as much a part of setting the Sterkarm scene as details of their food, clothing, furniture and buildings.

I wasn't too purist, though. In A Sterkarm Handshake, Per Sterkarm is hurrying through the alleys of the tower, on his way to Andrea's 'bower' (which just means 'bedroom' or 'sleeping place.) He thinks he's on a promise.

Oh, pleasant thoughts come to my mind

As I turn back smooth sheets so fine,

And her two white breasts are standing so

Like sweet pink roses that bloom in snow.

The second book, A Sterkarm Kiss ends with the lines:

For there's sweeter rest

On a true-love's breast

Than any other where.

Neither of these quotes come from the Border ballads, although folk-song is, by its very nature, hard to date or pin down to a specific place. The first verse, as far as I know, comes from 'The Factory Maid.'

I'm a hand-loom weaver by my trade,

But I'm in love with a factory-maid,

And could I but her favour win,

I'd break my looms and weave with steam.

This dates it, roughly, to the late 18th or 19th century and means that this version is

likely to have been a 'broadside ballad.' These were lyrics, printed on the long sheets of paper which gave them their name. Often written about hot topics of the day, such as industrialisation, they were sold in market-places. There was no music but the name of some well-known tune would be given. 'To be sung to the tune of...'

|

| Mayhew's broadside ballad seller |

The lines about the true-love's breast come from a song with a beautiful tune, which I know as 'Searching for Lambs.' (This being what 'the loveliest maid that e'er I saw' was doing when her lover walked out one midsummer morning.) It's very hard to guess at a date for the lovely maid and her ewes, but the song doesn't have that robust mix of extreme vengeful violence and the supernatural that typifies the Border ballads, so it's probably later.

The date for my Sterkarms is about 1520 (though there were reivers long before and after this date.) Some of the songs I quote are certainly later and can be roughly dated to the late 1700s, but this doesn't mean that the Sterkarms wouldn't know something close to these lyrics and tunes. I justify my inclusion of them by the way that elements of folk-tales and ballads 'migrate,' from song to song and tale to tale over long periods of time.

The songs and stories were spread by word of mouth. If a singer or story-teller couldn't remember a detail, they invented their own. Or inserted a verse they could remember from another song. They might also take a verse from one song and put it into another simply because they liked it. They might change an ending to make it happier (see Johnny of Briedesley below) or change the relationships within a song, for example, having the hero murdered by his mother instead of his lover.

The same applies to the music. If they couldn't remember a tune, then they set the words to another or made up a variation. Other lyrics and tunes were updated. These tried-and-tested old tales can go on for centuries. Some researchers think some folk-tales go back to the Bronze Age.

Some old songs almost seem to be compilations of verses:

The songs and stories were spread by word of mouth. If a singer or story-teller couldn't remember a detail, they invented their own. Or inserted a verse they could remember from another song. They might also take a verse from one song and put it into another simply because they liked it. They might change an ending to make it happier (see Johnny of Briedesley below) or change the relationships within a song, for example, having the hero murdered by his mother instead of his lover.

The same applies to the music. If they couldn't remember a tune, then they set the words to another or made up a variation. Other lyrics and tunes were updated. These tried-and-tested old tales can go on for centuries. Some researchers think some folk-tales go back to the Bronze Age.

Some old songs almost seem to be compilations of verses:

Oh had I wist, when first I kissed

That Love had been so ill to win,

I'd have shut my heart in a silver cage

And pinned it with a silver pin.

The men of the forest, they asked it of me,

How many sweet strawberries grow in the salt sea?

I answered them well, with a tear in my e'e;

'As many fish swim in the forest.'

When cockle-shells turn silver bells

When fishes swim from tree to tree

When ice and snow turn fire to burn

It's then, my love, that I'll love thee.

The writers of broadside ballads certainly drew on these old songs too, re-using verses to save time as they tried to make a living. So because a verse about a factory maid was published in a broadsheet ballad in, say 1810, it doesn't mean that something very like it wouldn't have been known very much earlier.

And just because a gentle love song doesn't mention treachery, incest, fratricide, infanticide or any of the other -cides so popular in the Border ballads, it doesn't mean it wasn't known on the Borders. Even there, they had their quieter moments.

I thought it a pity that my readers couldn't hear the songs that are quoted so frequently throughout the Sterkarm books - and then realised that there was a way for me to share them. If you have a Facebook or Spotify account, here's a link to my playlist for the Sterkarm books.

The songs here are the best versions I could find on Spotify of the ballads I quote, but they aren't definitive. For instance, in the linked Johnny of Breadiesley, sung by Ewan McColl, Johnny kills seven enemies and rides away triumphant. In other versions, he is killed: His good grey hounds are sleeping,/ his good grey hawk has flown,/ a grass green turf is at his head,/ and his hunting all is done. The verse quoted above, from January, [The higher on the wing it climbs...] also has slightly different words in the recording by June Tabor.

If you like songs about murder, revenge killings and executions - plus the occasional love-song - and if you like deep-dyed folk - this is for you.

I thought it a pity that my readers couldn't hear the songs that are quoted so frequently throughout the Sterkarm books - and then realised that there was a way for me to share them. If you have a Facebook or Spotify account, here's a link to my playlist for the Sterkarm books.

The songs here are the best versions I could find on Spotify of the ballads I quote, but they aren't definitive. For instance, in the linked Johnny of Breadiesley, sung by Ewan McColl, Johnny kills seven enemies and rides away triumphant. In other versions, he is killed: His good grey hounds are sleeping,/ his good grey hawk has flown,/ a grass green turf is at his head,/ and his hunting all is done. The verse quoted above, from January, [The higher on the wing it climbs...] also has slightly different words in the recording by June Tabor.

If you like songs about murder, revenge killings and executions - plus the occasional love-song - and if you like deep-dyed folk - this is for you.

Comments