The Geography of Words - Guest Post by Jacey Bedford

Writing

science fiction and fantasy often involves worldbuilding. Sometimes we take a

concept, strip it right down to basics and invent a planet where the sea is

pink, the sky is upside down and the dominant life form has seven tentacles and

inhabits arid polar regions which have daytime temperatures of 60 Centigrade.

Our hero is a brave tardigrade with a serious Walter Mitty complex and its love

interest is a tri-gendered cephalopod with stunning bioluminescence that

screams, 'Come and get me, baby!'

Other times we base our world on

something closer to home. Our characters are human, living (maybe) five hundred

years in our future or two hundred years in our past, but they are recognisably

like us and they come from places that we might easily recognise.

We

might set our fantasy on this earth, in this century (much urban fantasy

occupied this niche) or we might use a medievaloid setting which is

recognisably British or European, or—increasingly popular—a non-European

setting in Africa, Asia or the Far East.

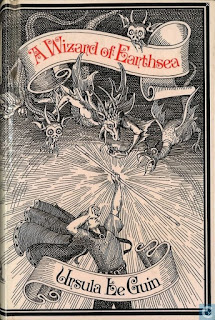

Even

when writing a second-world fantasy like (say) A Wizard of Earthsea, the laws

of physics are recognisable as our own and the land—mountains, rivers, lakes,

valleys, deserts, oceans--looks as though it was formed in much the same way as

our mountains, rivers lakes etc. were formed. That means it's a world with wind

and weather, continental drift, vulcanicity, recurring ice ages etc. All of

that may be completely incidental to the actual story, of course, but it gives

us a setting we can grok, deep inside.

But

how do we decide on a setting, and how do we build a world?

If

we're going to base it on part of this world that we know, it helps to have a

jumping off point Though you might never need to explain this in your book, you

should know it. My Rowankind trilogy opens in 1800, in a world like ours but

with an undertow of magic. Some things are the same. King George is bonkers, Britain

is at war with Napoleonic France. America has won its freedom. The industrial

revolution is in its early years with steam engines used for pumping water out

of mines, but not yet used to power locomotives.

If

we're going to base it on part of this world that we know, it helps to have a

jumping off point Though you might never need to explain this in your book, you

should know it. My Rowankind trilogy opens in 1800, in a world like ours but

with an undertow of magic. Some things are the same. King George is bonkers, Britain

is at war with Napoleonic France. America has won its freedom. The industrial

revolution is in its early years with steam engines used for pumping water out

of mines, but not yet used to power locomotives.

But where does the magic come from?

Has it always been there? Yes, it has, but for the last two hundred years it's

been strictly controlled by the Mysterium. Why? It all stems from the time of

the Spanish Armada in 1588. Something happened to bring knowledge of magic and

its possibilities to Good Queen Bess, and her spymaster, Sir Francis

Walsingham. If I told you exactly what you wouldn't need to read the first book

of the Rowankind, Winterwood, and I

hope you do.

Two

hundred years after the formation of the Mysterium, only licensed witches are

allowed to perform small magics from carefully controlled spell books. Enter

Ross (Rossalinde) Tremayne, my cross-dressing female privateer captain. Ross

would gladly have registered as a witch when she turned eighteen, as the law

said, but she was busy eloping instead. Now, seven years later, she's a widow,

and she's captain of the Heart of Oak, accompanied by the jealous ghost of her

late husband and a crew of barely-reformed pirates. When she pays a deathbed

visit to her estranged mother she receives a task she doesn't want and a half

brother she didn't know she had. And then there's that damned annoying wolf

shapechanger, Corwen. (Don't call him a werewolf, he gets very annoyed, because

he's NOT moon-called!)

Ross

and Corwen's story moves forward in Silverwolf

and the worldbuilding widens. A race of magical people, the Rowankind, have

been freed from bondage and their talents for wind and weather magic have the

potential to change Britain's developing industrial revolution. Why would we

need steam engines, when the Rowankind can lift water from the depths of a mine

by magic? That's almost incidental to Ross and Corwen's personal story, but I

have to consider how something like that could change future history. It echoes

through Silverwolf and the final book in the trilogy, Rowankind, due from DAW in November 2018.

My Psi-Tech trilogy, Empire of Dust, Crossways and Nimbus, all published by DAW, is set

five hundred years in the future when megacorporations more powerful than any

single planet have raced across the galaaxy to gobble up planets suitable for

colonisation. Their agents are psi-techs, humans implanted with telepath

technology. These elites are looked after from cradle to grave, until—that

is—they step out of line. Cara is a rogue telepath fleeing Alphacorp, Ben is a Trust

company man through and through, until the Trust tries to kill him. Why? It's all

about money and resources. Cara takes refuge with Ben on his colony mission,

thinking she can keep her head down for a few years until Alphacorp has stopped

hunting her, but trouble comes looking for both of them.

So

in my psi-tech universe, I'm not so much worldbuilding as building multiple worlds

linked by a network of jump gates. I'm also building enhanced humans who might,

on the whim of their company, be sent for neural reconditioning to adjust their

attitude—and that's not good. But despite the wetware implants, they're still

human, gloriously, awkwardly so.

So what am I working on right now? The Amber Crown is a standalone fantasy

set in the mid 1600s in a place not unlike the Baltic States with a few

significant differences. There's magic and political intrigue, a cast of

diverse characters and a missing queen. Worldbuilding for this has been

interesting. I've done a lot of research on costume, food and customs. I've

discovered some delightfully bonkers facts like the existence of the Polish

Winged Hussars, who rode into battle with huge wings strapped on to their

backs, and for more than a century were the best cavalry in all of Europe.

Three thousand Polish Winged Hussars broke the might of the Ottoman army at the

Siege of Vienna in 1683. That's a gift to a writer. Thank you, history.

Jacey

Bedford is a British writer, published by DAW in the USA. She writes both

science fiction and fantasy and her novels are published by DAW in the USA. Her

short stories have been published on both sides of the Atlantic in anthologies

and magazines, and some have been translated into an odd assortment of

languages including Estonian, Galician and Polish.

Jacey's a great advocate

of critique groups and is the secretary of the Milford SF Writers' Conference,

an intensive peer-to-peer week of critique and discussion held every September

in North Wales. (http://www.milfordSF.co.uk)

She lives in an old stone

house on the edge of Yorkshire's Pennine Hills with her songwriter husband and

a long-haired, black German Shepherd (a dog not an actual shepherd from

Germany). She's been a librarian, a postmistress, a rag-doll maker and a folk

singer with the vocal harmony trio, Artisan. Her claim to fame is that she once

sang live on BBC Radio 4 accompanied by the Doctor (Who?) playing spoons.

You can keep up with Jacey

in several different ways:

- Website:

http://www.jaceybedford.co.uk,

which includes a link to her mailing list.

- Blog:

https://jaceybedford.wordpress.com/

- Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/jacey.bedford.writer

- Twitter:

@jaceybedford

Comments

And I LOVE the idea of your heroine being accompanied by the jealous ghost of her dead husband.

Winterwood looks fascinating... love that cover!