Diana Athill's Extraordinary Life, By Dipika Mukherjee

I “found” Diana Athill rather late in my reading life, and I

have V.S. Naipaul to thank for it.

A week after Naipaul’s death, Athill wrote an essay about being Naipaul's editor. She described admiring Naipaul’s work but disliking the man, and there was such certitude in her storytelling voice that I was immediately hooked.

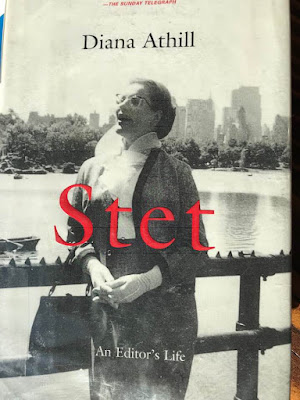

I hunted down Stet.

Part historical overview of British publishing, part break-room office gossip,

it was riveting. Athill had been a well-regarded British editor for fifty years, and her own literary career took off after her retirement; this book was published when she was 83 years old. When I read Stet, Diana Athill was already a hundred years old, yet meteoric in the British

literary scene. She became my hero; this rare, ageless female writer, one who discusses literary nuances and sexual romps with great pleasure.

Athill’s editorial training is evident in every crisp, well-crafted

sentence. When she announces her inability to care about

money – and as most writers earn so little from writing that financial optimism seems a prerequisite for this profession -- she phrases it delightfully so:

“Somewhere within me lurks an unregenerate creature which feels that money

ought to fall from the sky, like rain. Should it fail to do so – too bad; like

a farmer enduring droughts one would get by somehow, or go under, which would

be unpleasant but not so unpleasant as having blighted one’s days by worrying

about money.”

She has chapters for the writers she edited --

Naipaul, Rhys, Updike – and through her, I discovered the enchantment of The

Wide Sargasso Sea. Jean Rhys had a troubled life and left the world some

exquisite prose, and Athill has a great deal of respect for even the

most difficult of writers :

“The chief difference, it seems to me, between the person

who is lucky enough to possess the ability to create – whether with words or

sound or pigment or wood or whatever – and those who haven’t got it, is that

the former react to experience directly and each in his own way, while the

latter are less ready to trust their own responses and often prefer to make use

of those generally agreed to be acceptable by their friends and relations. And

while the former certainly include by far the greater proportion of individuals

who would be difficult to live with, they also include a similarly large

proportion of individuals who are exciting or disturbing or amusing or

inspiring to know.”

Athill’s imaginary world was boundless, and she looked for writers who opened hearts and minds, especially in difficult times:

“...why books have meant so much to me. It is not because of

my pleasure in the art of writing, though that has been very great. It is

because they have taken me so far beyond the narrow limits of my own experience

and have so greatly enlarged my sense of the complexity of life; of its

consuming darkness, and also – thank God – of the light that continues to

struggle through.

Stet is an apt title for her memoir; from the Latin “let

it stand” it is used on corrected manuscripts to indicate that a correction or

alteration should be ignored. This book was, in her own words, meant to live on even after her own life was erased, so that she would “feel a

little less dead if a few people read it”.

More than a few people have already read Stet, and those

that haven’t yet, a treat awaits.

Thank you for your words, Diana Athill. The literary world is an immeasurably better place for having had you in it.

Dipika Mukherjee is a writer and sociolinguist. Her work, focusing on the politics of modern Asian societies and diaspora, includes the novels Ode to Broken Things (Repeater, 2016) and Shambala Junction (Aurora Metro, 2016).

Comments

Stet left a huge unanswered question (as Athill intended!). If her difficulty with V S Naipaul (clearly a tricky character himself) constituted the 'second-worst' misjudgement she made in her publishing career, WHAT WAS THE WORST? Did she turn down J K Rowling? Jacqueline Wilson? Colin Dexter? We will never know.

Wonderful post! You evoke Athill's brilliance vividly.