Duvets --- Susan Price

|

| Wikimedia: a down feather |

Last month, I wrote about the art of Jack Frost and how he used to paint the windows in the freezing winters of my childhood.

That started me thinking more about the way things were back then...

Our bedrooms were freezing in winter. The cold was painful. My mother used to heap blankets on top of us until we were laminated to the mattress. When I say we could barely move for the weight, I am not exaggerating. Thick woollen blankets are heavy. We were pinned.

And yet we were still cold.

I remember lying awake for hours, unable to sleep because I was too cold. Cold feet, cold knees, cold bum, cold ears, cold nose.

After an age, your own body heat would create an egg-shell thin border of warmth around you... But if you moved even slightly, if a toe or finger strayed over that thin border of warmth, then you leaped with shock at the thrilling, cold-ribbed regions of ice-sheet beyond. And your shocked movement shifted the crushing layer of blanket ever so slightly and let in cold gales. Misery.

On especially cold nights, Mum would give us a hot-water bottle. You would cling to it, a tiny spot of warmth in the cold. It did nothing to heat the ice sheets a millimetre beyond the place where you lay.

And the bottle quickly went cold. From almost too hot to touch to almost too cold to touch seemed to take about half-an-hour. Then you would kick the cold-water-bottle to the bottom of the bed. Occasionally cramp made you stretch out a leg and touching the bottle with your toes made you flinch. It was like touching a block of ice.

Needing the loo was torture. You had a choice of leaving the hard-won skin of warmth for the freezing bedroom, landing and bathroom and then, shivering, return to a bed that had gone cold again. Or you could huddle in that tiny area of warmth until your bladder burst. Your decision.

And then, when I was 18, Britain joined the EU. A number of shifts seemed to stem from that, such as the quality of restaurants improving. There had always been high-end restaurants but I'm talking about the general standard of small local restaurants and cafes outside London and the South East.

Pubs too. Previously, if a pub served wine at all, then it was stuff that would take the shell off an egg. Wine was for women and pubs weren't for women, so why bother providing anything other than red vinegar?

|

| Wikimedia |

Almost overnight, it seemed, pubs got coffee machines. Cafetieres. I suppose more people were spending more time in Europe. There was something called 'freedom of movement.' And they returned from their free movement better informed and expecting a higher standard.

At around this time, I'd left school and found a job. I was also earning money from my first book. I felt pretty flushed with cash. So when I started hearing about these strange things called duvets, I was intrigued. You put them on the bed, it seemed, just the one of them, not a heap. And they were light, yet kept you warm. Could such a thing be?

No, surely not. But my aunt, who had married a Pole, said, yes, it could. Through her husband she knew many of the local Polish community, exiled from their homeland after WW2. Marooned in Britain, they had not been slow to supply themselves with duvets, imported with great trouble and expense from 'abroad'. Polish winters, as my uncle often told me, were very cold, much colder than in Britain, but they were dry. Miserable British winters were not only cold, but foggy, claggy and wet. Polish houses were, sensibly, designed for cold winters. British houses were draughty, cold and damp. Unthinkable to face a British winter without a duvet.

As another cold, foggy, claggy wet British winter was approaching, I decided to blow some of my cash on one of these duvets for myself. And reader, it was heaven.

Beside a flattening pile of heavy blankets, it seemed insubstantial. It was far too light to crush you. And yet, as it softly folded around you, it quickly made you too hot! And not just for a millimetre on either side. You could stretch out, turn over, take up whatever position you liked, and the soft, light duvet cuddled around you and kept you warm. A wonder.

I was so impressed that I bought my parents a duvet for Christmas, but gave it to them right away, at least a month before. They were dubious. If duvets were so great, how come the British had stuck with blankets for so long? But, not to seem ungrateful, they tried it out one night -- and got up the next day, went forth and bought a duvet each for my brother and sister. I don't think the beds ever saw a blanket again.

Yet sometimes the bed was still a bit chilly on first getting in, and I'd take a hot-water bottle under the duvet with me on really cold nights, pushing it aside when I got too hot. So it was I discovered that after spending a whole night under a duvet, the hot water bottle was still warm the next morning.

Not hot, I grant you. But certainly warm to the touch and therefore slightly above blood heat. Whereas under heavy piles of blankets, hot water bottles had gone stone cold in minutes. Nothing better demonstrated the vastly superior insulation of the duvet compared to the blanket.

Yet the British had no truck with duvets for hundreds of years. I've read that it's because we're a conservative, xenophobic and stingy nation and duvets were newfangled, foreign and expensive.

True. Yet the British had duvets once upon a time. In the Orkneys and the Shetlands, people used to collect the eider down from the nests of eider ducks. (The so-called 'Frankie Howard duck' because it goes, 'Ooo-Oo! Oo-ooo! -- a joke for the older generation.)

Feathers were saved from the plucking of ordinary poultry too: chickens and geese. These were used to stuff a large sack to make a mattress or 'feather bed.' A quilt or eiderdown was a slightly less stuffed sack which sleepers spread over themselves. Since these sacks had no structure to prevent the feathers clumping, they had to be shaken every day -- this is supposedly what 'Mother Goose' is doing when it snows. She is shaking out her feather bed and quilt.

Yet, at some point the Great British Public abandoned light, comfortable duvets and went wholesale for heavy blankets with all the insulation of a wide open door. Why? My Polish uncle's explanation was simple: the British were mad. It was a well known fact. Trapped on their narrow, wet, grey little island, they went a bit loopy.

Not the cuddly, eccentric, 'Ooh, what are we like' sort of mad either. Just a half-baked, cut-off-your-own-nose-to-spite-your-face sort of mad. Even twenty years later I met Britons who wouldn't have a duvet in the house because they were 'untidy'. A bed looked nicer made up 'properly' with blankets and sheets, it seemed. Never mind about being warm. You're meant to be tidy in this life, not warm.

I can't leave the subject of duvets without considering the vexed question of How Do You Put On A Duvet Cover? There are videos all over YouTube, instructing you in this difficult art. I've seen accounts that involved standing on the bed or a chair while you shake the duvet down inside the cover. Others advise you to clip the corners of cover and duvet together with clothes pegs while you wrestle with the rest. Still others tell you to 'roll the covers on like a sock.' Or to 'roll cover and duvet up together like a burrito,' which somehow puts the duvet inside. (I couldn't sustain enough interest to find out how.)

I'll tell you how the Poles do it, those cold weather survival experts. Or how they used to do it, anyway, back in the early 1950s, when the international postal service was chokka with Polish duvets and covers being delivered to sleepless exiled Poles with nothing to keep them warm except several tons of British blankets.

I couldn't find a photo, so you'll have to put up with my bad drawing. The pale blue thing is the duvet cover. See that St. Andrew's cross in the middle? That represents slits made in the cover. Through them, you can see the white duvet inside.

The slits were hemmed and often edged in lace. To insert the duvet, you placed the duvet on top of the cover, roughly lining up sides and corners.

Then you lifted the triangles of material made by the slits in the cover and pushed the duvet inside, corner by corner, edge by edge.

Simples! (Said with a Polish accent.)

I've never seen a duvet cover like this on sale anywhere in Britain. Figures.

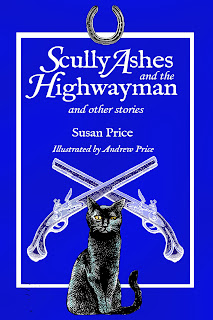

I've finally managed to produce an illustrated ebook of Scully Ashes and the Highwayman.

Comments

I think the Remain camp should have made more of the coffee and all the European food options that we didn't have before going into the EU!