Hopping by Sandra Horn

We encountered our first mists of the season last weekend on

our way back from a jaunt to Dorset, we’ve been eating the new damson jelly, and

the russet apples are ripe so there’s your mellow fruitfulness. In a couple of

weeks we’ll be heading upcountry to the North Lakes, and if we’re lucky, we’ll

be driving towards more and more glorious leaf colour. Autumn.

If I could roll back almost 70 years, I’d be getting up before it was quite light and taken to Nan’s house to get the hoppers’ bus out to Mas’ Bishop’s hop gardens between Boars Head and Eridge.

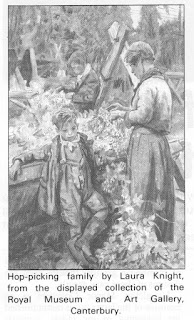

Mr Bishop would have arrived at the house some weeks before and addressed Great Gran: ‘Will you pick this year, Missus?’ ‘Yes, we’ll pick.’ ‘How many?’ Great Gran would tot us up – everyone, except the working men and small babies. The box with the primus stove, tea, slab of fruit cake and cups would have been sent on beforehand and we had the bread and cheese with us. We arrived to the first cutting of the bines, which were wet with dew and came down with a satisfying crash, spraying dewdrops and caterpillars as they fell. The caterpillars were much prized. I’ve no idea what kind they were. They were brown and hairy. We called them hop dogs. We always tried to get as close as we were allowed to the falling bines, so we could get soaked in cold dewdrops. Then it was to work, to find our sacking bins. The older children picked alongside the grownups and the smaller ones picked into Great Gran’s upturned umbrella. When I was very small, I was given Great Grandad’s trilby hat to pick in until it was full of hops - but no leaves or twiggy bits, which were a cause of shame.

Once I’d picked a hatful and the others had filled the umbrella, we could go and play. There was a stream at the bottom of the field and we spent many happy mornings fishing for tiddlers, which we never caught. There were sloes in the hedgerow which we soon learned to avoid. They were unbelievably bitter and teeth-skinning. There were also hazelnuts, as yet not fully ripe, but we kept opening one after another, hoping to find a nut rather than a pale half-formed, sour, milky sliver. Then we were called to eat our bread and cheese and cake and drink hot sweet tea before the afternoon picking. From time to time, the bins were emptied into bushel baskets and then pokes and each person’s pickings were tallied. The men loading up the baskets were watched closely to make sure they didn’t pack the hops down too tight, which would have cheated us of our earnings – which in one notable year reached the dizzy heights of a shilling a bushel. Off went the hops to the oast to be dried and at the end of the day we got back on the bus, out hands black, sticky and stiff with pollen. When we were back home, Nan put liberal dollops of butter in our palms and we rubbed it well in to loosen the pollen before washing our hands. The black stain stayed on for quite a while, though. I loved it and went on going with Nan long after the others were at work and unable to come with us. I had to stop when I was about 12 and my new school holidays didn’t coincide with the hop-picking. In my first year at the school, I went picking for the first few days before term started, but then there was the problem of the black hands…

Hops

The dandelion clocks are all blown. Hops waft sleep-scented pollen on the air. We leave warm beds before it’s light, to spend the long days picking the hops, staining our scratched hands inky-black. Bines like Jack’s beanstalk climb towards the sky. Knives on long poles slash the tops. The bines crash down, hissing, spraying dewdrops, spiders, caterpillars up into the air. We dance, shrieking, through the icy tickling shower.

The dandelion clocks are all blown. Shadows lengthen, days grow shorter. Early morning mists and chill. Leaf-colours seep through fading green. Silvery tiddlers dart around the stream. We hunt the quick, elusive fish with our jam-jars, school caps, open hands. We chase, splash, giggle, shout, never, ever catch.

The dandelion clocks are all blown. Spiderwebs are hung with dew, bright as diamonds in the hedge. Bend a withy twig into a hoop, scoop them up. Look, we’ve made a mirror!

Morning after morning we plunder the hedge for sloes, nuts, spiderwebs, chill our feet and fingers in the stream – all of it for pleasure in the Summer’s dying days.

Comments

What happens now, I wonder? Are all the hops picked mechanically? It was clearly hard work for the families but bound them together in such an enriching (not financially I guess!) experience.

In Liverpool it was called 'sagging'.