Railways I have loved - Dennis Hamley

Yes, so many of them - and from such an early age too. I remember watching the old 'push-and pull' chuff past my bedroom window before I was five - two green Southern Railway coaches with, between them in a steam sandwich, a 'Terrier' tank engine from the old London, Brighton and South Coast Railway.

Then a mighty experience: an epic (to six-year-old me) journey to the Lake District from St Pancras (Euston had been bombed) - an unconscionably long train of maroon coaches hauled by a hissing monster which seemed to me to be too large for this puny world. This wasn't a holiday: my father, a Post Office engineer, badly shell-shocked after the air raid on Biggin Hill, was being sent there to recuperate by the Air Ministry, who wanted him back at work in a fit state.

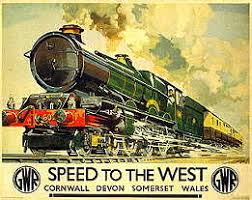

And then, when the war was over, two magical journeys, images of escape and freedom, to South Wales, in chocolate and cream Great Western coaches, hauled by shining Castle class locomotives, which more than anything else, except the 1945 General Election, meant entry to a new world to me.

Porthmadoc station has, to me, a slightly unreal quality. It seems at first a perfectly normal railway station, except that the platforms are lower, but it's home to some extraordinary pieces of machinery and anyone seeing them for the first time might be pardoned for asking what on earth they are.

The two railways, both with gauges of one half-inch less than two feet, meet here. The Ffestiniog has a long honourable history which started in 1832. It earned most of its money transporting slate from Blaenau Festiniog to Porthmadoc but was also important transport until buses and cars killed it in the 30s. The decline of slate mining finally finished it off and it closed in 1939.

By comparison, the WHR's history is chaotic. It started nearly a century after the Ffestiniog, was beset by difficulties, never made a profit, had little slate or goods traffic, wasn't supported by passengers and faded out unloved, unsuccessful and unmissed.

But the great preservation movement started in the 50s with Tom Rolt's plan to reopen the Tal-y-Llyn and now it has mushroomed into 'The Great Little Trains of Wales', not just tourist attractions but whole ways of life.

Sadly not a sandwich, but redolent of those times none the less.

Then a mighty experience: an epic (to six-year-old me) journey to the Lake District from St Pancras (Euston had been bombed) - an unconscionably long train of maroon coaches hauled by a hissing monster which seemed to me to be too large for this puny world. This wasn't a holiday: my father, a Post Office engineer, badly shell-shocked after the air raid on Biggin Hill, was being sent there to recuperate by the Air Ministry, who wanted him back at work in a fit state.

In black and white as contemporary technology demanded. But it certainly wasn't black and white to me.

And then, when the war was over, two magical journeys, images of escape and freedom, to South Wales, in chocolate and cream Great Western coaches, hauled by shining Castle class locomotives, which more than anything else, except the 1945 General Election, meant entry to a new world to me.

Like waking up after a bad dream

Yes, these were my dominant childhood images of excitement, romance and escape. I felt it in mundane short trips, feeling slightly threatened but with the pleasant frisson of defying authority by ignoring the Is Your Journey Really Necessary notices plastered over every station. And I still feel it - on Eurostar, French TGVs, German ICE trains, Amtrak from Washington to Boston, as well as the still slightly alien privatised railways here. Very recently, we had the mild sense of a significant event in history when we travelled to Marylebone on the very first day of Oxford's new London service in October. No more interminable signal stops outside Reading to let expresses full of smiling Devonians through. And it meant the Old Great Central was coming back, to be followed by reinstatement of the old East-West Oxford to Cambridge Varsity Line. When I was first teaching, I found myself president of the Railway Club at every school I entered and my annual lecture on the Great Central Railway, (my favourite railway, the last main line, savagely done to death by a philistine British Railways Board which still regarded it as an upstart in 1964. A crime at last being expiated) was always eagerly looked forward to. By me, at any rate.

And then of course there are the Great Railway Journeys of the World. I've only been on two of the official list, the Jacobite from Fort William to Mallaig, with its beautiful K3 class 2-6-0, once of the LNER, and the Tranz-Alpine, Greymouth to Christchurch, coast-to-coast in the South Island over the Southern Alps. Both magnificent. We want to try the Overlander from Auckland to Wellington as well. By the time you read this, we might have!

And then there are the preserved railways, where the true railway heart still beats. I have to come clean and say that I've never been an actual volunteer. I suppose I didn't want my daughter to say 'My father looks an absolute prat' when she saw me in my ticket-collector's uniform. But how superb they are. The (real) Great Central, Leicester to Loughborough, Loughborough to Nottingham, separate now but at last they have money and planning permission for a new bridge to connect them and restore a proper main line 40 miles long. Bluebell, Watercress, Strathspey, North Norfolk, North Yorkshire Moors, Severn Valley, East Lancs, Llangollen, Keighley and Worth Valley, and so many more. All standard gauge.

But the greatest delights are the narrow gauge railways. In Wales they were buit to carry slate and also to provide a basic passenger service. And they are far cheaper to build. But that doesn't mean there's anything cheapjack about them. The Tal-y-llyn, the Rheidol Valley, the Welshpool and Llanfair were once vital. Then their day was gone and one by one they closed. But now they are back, restored, and we can see them for the magical things they always were.

My birthday treat this year was a short stay in North Wales. Our base was Porthmadoc, where the Festiniog railway and the Welsh Highland Railway meet. But first to Portmeirion, where the tone for our little holiday was set.

And then of course there are the Great Railway Journeys of the World. I've only been on two of the official list, the Jacobite from Fort William to Mallaig, with its beautiful K3 class 2-6-0, once of the LNER, and the Tranz-Alpine, Greymouth to Christchurch, coast-to-coast in the South Island over the Southern Alps. Both magnificent. We want to try the Overlander from Auckland to Wellington as well. By the time you read this, we might have!

And then there are the preserved railways, where the true railway heart still beats. I have to come clean and say that I've never been an actual volunteer. I suppose I didn't want my daughter to say 'My father looks an absolute prat' when she saw me in my ticket-collector's uniform. But how superb they are. The (real) Great Central, Leicester to Loughborough, Loughborough to Nottingham, separate now but at last they have money and planning permission for a new bridge to connect them and restore a proper main line 40 miles long. Bluebell, Watercress, Strathspey, North Norfolk, North Yorkshire Moors, Severn Valley, East Lancs, Llangollen, Keighley and Worth Valley, and so many more. All standard gauge.

But the greatest delights are the narrow gauge railways. In Wales they were buit to carry slate and also to provide a basic passenger service. And they are far cheaper to build. But that doesn't mean there's anything cheapjack about them. The Tal-y-llyn, the Rheidol Valley, the Welshpool and Llanfair were once vital. Then their day was gone and one by one they closed. But now they are back, restored, and we can see them for the magical things they always were.

My birthday treat this year was a short stay in North Wales. Our base was Porthmadoc, where the Festiniog railway and the Welsh Highland Railway meet. But first to Portmeirion, where the tone for our little holiday was set.

Portmeirion. Slightly-skewed fantasy. Beautiful, eccentric, but, underneath it all, disturbing (that's me in the middle looking disturbed). Even, I think, somehow terrifying. Apart from the last two adjectives, so are the Railways.

,

LINDA of the Festiniog. Beautiful, eccentric. Slightly skewed fantasy.

Porthmadoc station has, to me, a slightly unreal quality. It seems at first a perfectly normal railway station, except that the platforms are lower, but it's home to some extraordinary pieces of machinery and anyone seeing them for the first time might be pardoned for asking what on earth they are.

The two railways, both with gauges of one half-inch less than two feet, meet here. The Ffestiniog has a long honourable history which started in 1832. It earned most of its money transporting slate from Blaenau Festiniog to Porthmadoc but was also important transport until buses and cars killed it in the 30s. The decline of slate mining finally finished it off and it closed in 1939.

By comparison, the WHR's history is chaotic. It started nearly a century after the Ffestiniog, was beset by difficulties, never made a profit, had little slate or goods traffic, wasn't supported by passengers and faded out unloved, unsuccessful and unmissed.

But the great preservation movement started in the 50s with Tom Rolt's plan to reopen the Tal-y-Llyn and now it has mushroomed into 'The Great Little Trains of Wales', not just tourist attractions but whole ways of life.

Merddyn Emrys, one of the unique Double Fairlies

A Beyer-Garratt from Zimbabwe.

I said earlier that Porthmadoc station has a slightly unreal air with its extraordinary machinery. Both the locomotive above and the one below typify this. If you don't know them already, take a good look. Merddyn Emrys. What can it be? It's got obvious railway engine bits on it but it looks like Dr Doolittle's 'Push-me-pull-you'. Skewed fantasy again?

And what's that weird object below? The bit in the middle looks like a railway engine, but why has it got its driving wheels so far away under those huge clumsy tanks at the front and the back? Are these contraptions railway engines or are they not?

A Beyer-Garratt from Zimbabwe.

Well, yes, they are. Two attempts to answer the same question. Having them together based at the same station is a unique circumstance, worth going to see for its own sake. There's a good reason, quite apart from giving tourists a good day out, for all the Welsh narrow gauge railways. Narrow gauge is not just cheap. It was then the only way to have proper transport for freight and people in mountainous places. But the railways will be full of steep gradients, which means power, and sharp bends, which means agility. However, trains aren't very good at going round corners so combining the two is very hard..

There were two answers, both of which are at Porthmadoc. The first was the Double Fairlie, designed by Henry Fairlie and built for, by and on the Ffestiniog at Boston Lodge. The first, Little Wonder, was built in 1869.

Really, quite simple.

Two boilers, two fireboxes which double the power and two sets of driving wheels, fore and aft, which swivel, so it is, relatively speaking, very powerful and also very flexible. Takes sharp bends a real treat. Still running after 150 years.

But the Welsh Highland Railway, it was quickly realised as the rebuilding continued, didn't have any locomotives of its own to do a similar job. One of the reasons why it closed so early was that it used old, worn out engines cast off from other lines which just couldn't keep it going. So they looked round the world and found the answer lying idle in Zimbabwe. Beyer-Garratts, They bought five and shipped them over.

The Beyer-Garratt design dates from 1911. Herbert Garratt's brainchild. Most were built by Beyer Peacock in Manchester. They consisted of one very big boiler and two swivelling separate steam engines at either end. It was even more powerful than the Fairlies. And there they were, superseded by diesels but still in good order because they were built in 1958, which means in the railway world, when translated into motoring terms, 'Low mileage, excellent condition, one careful owner.' They were also among the last ever built, so you can't get steam engines much more modern. ninety years newer that the first Fairlies, anyway.

The Fairlie, running light, slips through the station silently, like a railway ghost. The Garratt snorts and blasts impatiently, never letting you forget it's there, like some dyspeptic dragon. And when it steams out of Porthmadoc and crosses the main road, you can see the impatience on the faces of held-up drivers change to awe as this metal monster of legend trundles past with its impossibly long train on the first leg of its trek into the mountains. Aberglaslyn, Beddgelert, under the lee of Snowdon, then Dinas and finally over the flat plain to Caernarfon. a mighty journey.

Or the other way behind a Fairlie, over the Cob to Boston Lodge and the workshops, Tan-y-Bwlch, then the Llyn Ystradau Deviation, an extraordinary feature. When the hydro-electric power station was built, the original track was destroyed. So volunteers built a new route, which includes a tunnel (built by Cornish mining engineers) and an extraordinary spiral which doubles back to cross over itself. By any standard it's fine engineering: that it was done mainly by unpaid volunteers is wonderful. And it meant that the atmospheric slate-dominated Blaenau Festiniog was at last reconnected with the coast - a distinctively fitting terminus for this marvellous artefact.

Yes, it's no wonder I love the railways. When I edited the Young Oxford Book of Train Stories for OUP, I dedicated it to my grandson Joe with these words:

Or the other way behind a Fairlie, over the Cob to Boston Lodge and the workshops, Tan-y-Bwlch, then the Llyn Ystradau Deviation, an extraordinary feature. When the hydro-electric power station was built, the original track was destroyed. So volunteers built a new route, which includes a tunnel (built by Cornish mining engineers) and an extraordinary spiral which doubles back to cross over itself. By any standard it's fine engineering: that it was done mainly by unpaid volunteers is wonderful. And it meant that the atmospheric slate-dominated Blaenau Festiniog was at last reconnected with the coast - a distinctively fitting terminus for this marvellous artefact.

Yes, it's no wonder I love the railways. When I edited the Young Oxford Book of Train Stories for OUP, I dedicated it to my grandson Joe with these words:

. . .in the hope that both trains and stories will mean as much to him as they have for me.'

And that's my hope for everybody!

Comments

Isn't it ridiculous that rail-lines which were closed as being 'unnecessary' have now been restored and, run by volunteers, are doing that 'unnecessary' job?

I know a few people, for instance, who use the Severn Valley, not as a day-out, but as a passenger line. One friend often leaves his car at Bridgenorth, takes his inflatable canoe down the river to Arley, packs the canoe up in a rucksack and catches a steam train back to Bridgenorth to pick up his car. The canoe trip is the day out for him - the steam train is the transport that makes it possible.