Playing Devil's Advocate with the literary greats by Griselda Heppel

My A level English teacher once began a lesson with a

challenge: ‘Why should people read novels?’

Easy, we thought. ‘To

find out about the world.’

‘Say I’m someone

who works in an office, a bank, a business. I have my newspaper for that.’

|

| Who needs books? Photo by James Abbott from FreeImages |

‘To find out about

people, then; what makes them tick.’ ‘Feelings and emotions.’ ‘See what it’s

like to go through something you haven’t experienced yourself.’

All of these answers

– perfectly reasonable, we thought – he batted back like flies. ‘People! I know

all about them, believe me. Work with people every day. What can a story

someone has made up, all about characters they’ve also made up, tell me about life?

That stuff’s just for kids. Pure entertainment. I don’t need to escape into

fairy stories, thank you.’

It was a wind-up,

of course. Boris, as we called him (I have no idea why – it wasn’t his name and this was decades before the rise of Another, More Famous than He)

was passionate about literature, and introduced us to a wide variety of authors

before focussing on the set texts. But that day I learnt something about

complacency and naivety that has stayed with me. As an idealistic Eng Lit

student, I took it for granted that the last thing the great writers – Dickens,

Dostoevsky, the Brontes, Tolstoy, George Eliot – wrote for was something as trivial as entertainment.

Their purpose was to broaden our minds and sympathies,

make us question moral prejudices, maybe even change the world. What Boris’s devil’s advocate performance taught me was that, while these may indeed be

their aims, none of them is of the slightest use if the story doesn’t grab you

from the start. So far from being the last, entertainment has to be the writer’s

primary purpose. Stretching the reader’s understanding, leading us to feel the

characters’ problems, joys, pain, tragedy and loss as if they are our own – all

that falls into place along the way of a cracking good story. By scorning a

novel’s entertainment value, Boris’s theoretical character missed out, not only

on a lot of fun, but on the opportunity to practise empathy.

|

| Classic literary entertainment |

It’s a funny thing,

empathy. Do we enjoy reading stories because our sense of empathy is already

strong, or does reading stories make it stronger? While there must be lots of other

triggers in our lives – not just books – to feeling empathy, I am beginning to

think it’s like a muscle. Exercise it regularly or it’ll grow weak. And fiction

– as some teachers and librarians, who guide children to books for their

empathy value, understand – is a good exercise machine.

|

| Empathy... it's like exercising. |

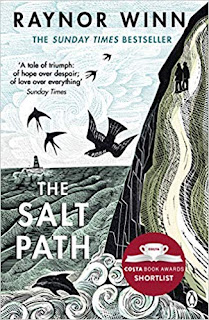

Recently I lent a

book I’d enjoyed to a friend who only reads non-fiction. The Salt Path is a memoir (so in

the right category for my friend) about a couple who, through some very foolish

financial misjudgement, had managed to make themselves homeless, and on a whim,

decided to escape their situation by going hiking. Cold, hunger, exhaustion and

serious illness accompany them on their journey, along with flashes of humour

and some hauntingly beautiful appreciation of the natural world.

Now, it’s always a risk to share an enthusiasm, but I was totally unprepared for how much my friend disliked this book. The reason? Since it was the couple’s own financial folly that set them off on their difficult journey, my friend had no sympathy with anything – good, bad, painful, sad, joyous – that happened to them on their way. If they were hungry, it was their own fault. Ditto, cold and wet. To be fair, the memoir, while being based on fact, had been shaped in a writerly way; author Raynor Winn had used the tools of fiction to give light and shade, glossing over details of the legal mess that begins the book, rounding off this self-imposed Pilgrim’s Progress with a satisfying conclusion. My friend, accustomed to hard facts and traditional historical narrative, clearly found this blending of genres suspicious and was therefore unable to enter into the world of the two main characters. Whereas I, more used to fiction, was happy to go with the flow, because it didn’t matter that the memoir wasn’t correct in every tiny detail; the vivid description of the couple’s journey, both physical and emotional, more than made up for that.

Now, it’s always a risk to share an enthusiasm, but I was totally unprepared for how much my friend disliked this book. The reason? Since it was the couple’s own financial folly that set them off on their difficult journey, my friend had no sympathy with anything – good, bad, painful, sad, joyous – that happened to them on their way. If they were hungry, it was their own fault. Ditto, cold and wet. To be fair, the memoir, while being based on fact, had been shaped in a writerly way; author Raynor Winn had used the tools of fiction to give light and shade, glossing over details of the legal mess that begins the book, rounding off this self-imposed Pilgrim’s Progress with a satisfying conclusion. My friend, accustomed to hard facts and traditional historical narrative, clearly found this blending of genres suspicious and was therefore unable to enter into the world of the two main characters. Whereas I, more used to fiction, was happy to go with the flow, because it didn’t matter that the memoir wasn’t correct in every tiny detail; the vivid description of the couple’s journey, both physical and emotional, more than made up for that.

In other words,

reading fiction appears to offer ways of exercising the empathy muscle that an

exclusive diet of non-fiction doesn’t. Frankly, in an ideal world, I’d make

reading fiction compulsory for all.

Comments

Fiction allows the reader to expand their knowledge of others’ lives in a way that is different than with non-fiction. The latter is informative. We read it to primarily glean knowledge, whereas fiction invites us to identify with characters, to consider their goals and desires instead of our own.

Though we read with the luxury of knowing that a book of fiction is not real, the ability to suspend our disbelief and feel for the characters speaks loudly to how we might behave in the real world.

:)

eden