Reading During the Lockdown - Guest Post by Peter Leyland

A recent article in the Guardian said research had shown that reading time spent on books has doubled in the lockdown. I am an avid reader and an auto/biographical narrative researcher in adult education, so I decided to examine the books I had been reading and whether they had helped me in any way to cope with the isolation the pandemic has caused

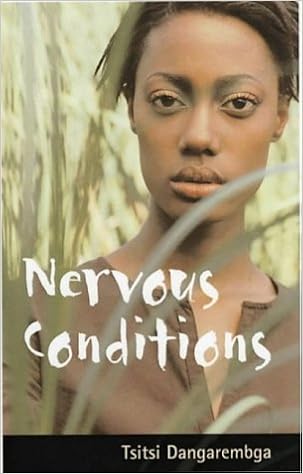

The first, Apeirogon by Colum McCann, a biographical novel set in the midst of the Israeli Palestinian conflict, was long and challenging. Although it gave me lots to think about, it failed to take off and like its many-sided title left me with more questions than answers. The second, Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga, was better and it was surprisingly easy for me to be taken inside the mind of Tambudzai, a young girl in Zimbabwe, and to encounter her struggles with her uncle and her parents, and her friendship with her cousin, Nyasha, as she begins to find herself while the country is simultaneously freeing itself from colonial rule.

But I was looking for something more: If you are in love you want to read about love; if you’re sad you want to read about and share someone’s sadness; If you’re in the middle of a pandemic which is shutting everyone up inside their houses, you might want to read about pandemics. I did, so I dug out a battered copy of The Plague by Albert Camus and began.

The book introduces itself through a narrator who is telling us the story of Dr Rieux and his attempts to deal with the sudden outbreak of a plague in the town of Oran in Algeria. It begins with reports about rats dying all over the town and how the number of the deaths increases until rat corpses are piling up everywhere. Then the disease transfers itself to humans and those infected develop a high fever and buboes in their armpits and groins which have to be lanced, a treatment which very few survive.

Slowly but inexorably the death toll rises, and as I read, I was reminded of our own death toll from Covid 19, rising and rising until our enormous lockdown took place. In Oran, similarly, the death toll rises until drastic action is taken to deal with it by The Prefect, the head of the municipality. The town is completely shut down, guards are posted, and gates are locked, and no-one can either go in or out. The narrator describes the excruciating death of a child from the disease, at which point I began to wonder why I had begun the book in the first place, but I persevered as I began to see the parallels with our own situation. In the novel, for instance, newspapers are said to be complying with instructions given to them and I thought of our own largely supine press talking vacuously about the heroism of nurses and care staff, rather than criticising those who had allowed the pandemic to become so virulent. ‘Optimism at all costs,’ says the narrator of The Plague about the press coverage of the situation in Oran and I wondered about the coverage of the clapping for the NHS and the much-feted heroism of Captain Tom.

In the book the journalist, Rambert, tries to escape the town in order to be re-united with his lover. With the help of his acquaintances like the footballer - and we might remember here that Camus was himself a goalkeeper - Rambert prepares his escape, but on a number of occasions his plans are thwarted. During a final attempt he changes his mind and decides to join his friend Dr Rieux in helping the plague victims. Together the band of workers continue to fight the disease. A high point is where Rieux and his friend, Tarrou go for a swim together at the end of a day of treating the victims and listening to rioting, a moment of respite from their struggle:

They dressed and started back. Neither had said a word, but they were conscious of being perfectly at ease, and that the memory of this night would be cherished by them both. When they caught sight of the plague watchman, Rieux guessed Tarrou like himself, was thinking that the disease had given them a respite, and this was good, but now they must set their shoulders to the wheel again.

This is when the book unlocked its meaning for me and moved me to a higher plane of understanding, that two men should bond in the face of such dreadful suffering and hardship. The mortality figures decrease but Tarrou himself succumbs to the plague after a long and painful illness. For Dr Rieux the death of his friend is then followed by a telegram with news of the death of his wife at the distant sanatorium where she has been recovering from an unrelated illness.

Dr Rieux becomes for me at this point a hero, someone with whom I could identify, someone with whom I could have a bond and be empathetic. In my narrative research about the power of literature undertaken with a group of students, one had explained the importance of the reader’s empathy with the characters, another had said that reading was an opportunity to step inside another mind. I had entered the mind of Dr Rieux.

Then comes the master-novelist twist, giving us the reason why we read great literature for answers. The narrator is revealed to be Dr Rieux himself. He has been putting together his story from as he tells us: what he saw himself; the accounts of other eyewitnesses; and documents that later came into his hands.

Now I too have to step into my narrative of what I have been reading and like Dr Rieux explain that the auto/biographical researcher uses him or herself as the material from which to collect data, provide analysis and reach conclusions. Looking back at the three books which I have described reading to you, well I am like Dr Rieux, a European male; I have a sense of vocation in that I have always been an educator with a desire to bring about change in my students, young or old, male or female. I think we need heroes like Captain Tom and the NHS nurses and doctors in our fight against the unknown features of the current pandemic. I think we can find them in literature.

Comments