Hold the Front Page! - Umberto Tosi

Those were the days, my friend. We thought they'd never end, when

printing was industrial and newspapers weren't media because we never

heard the word used that way. Editors chomped on cigars. Reporters

rat-tat-tat-tatted on their Remingtons and Underwoods, cigarettes

dangling from their lips, their white shirts open-collared and striped tie

loosened. They'd yell, “boy!” when they ran out of copy paper, or

were on a deadline and needed me to run their their hot sheets up to

the city desk as they typed furiously.

Teletype machines clattered incessantly in the glass-walled wire

room – AP, UPI, Reuters, INS – spitting out news of the world by

the ream. The copy boy – me – had to step lively to keep up.

Armed with a straight-edged length of leading, I would tear off

stories as the machines inched them out relentlessly – short and

long – and sort them quickly – local, state, national,

international – each destined for the wire basket of their

respective editors, No. 2 pencil at the ready. Red edges meant time

to switch out the fat roll of paper while trying not to to miss a

line.

|

| Linotype operators in a typical newspaper composing room of the early to mid 20th century. |

Every so often, a teletype machine would pause, then

ring-a-ding-ding-rrrring-rrring-rrring madly as a stuck

doorbell to announce an incoming “bulletin!” I'd run bulletins

to the editor – but only if I deemed them “important” – not every

damn one of them, or I'd get a dirty look and a dismissive snort,

because the wire services were always overreacting. God help me,

though, if I missed a big one. “Use your common sense, boy!” They

didn't teach any of this in journalism school. In fact, editors

looked askance a peach-fuzzed j-school grads. They much preferred

English or history majors, or better yet, a talented dropout who had

been around – by thumb and tramp steamer – worked on a small

paper or two. For example, it was said that the legendary ScottNewhall, flamboyant editor of the San Francisco Chronicle at that

time, would demand that prospective writers to show him

novels-in-progress rather than resumes.

It was 1956, and I was a copy boy for the Los Angeles Times, a

major metropolitan newspaper,

known at the time for running the most

editorial and advertising lineage of any in the world – and it

seemed to me that I was running through molasses in a dream world whose

distortions I'd only glimpsed in comic strips and movies. The copy

boy, as we knew it, is extinct. Nowadays they would call me an

intern and allow me the privilege of working for nothing. I'd

probably need an advanced degree to be a coffee gopher at what

newspapers continue to exist. But back then, I, at least, got minimum

wage and health insurance – enough to take care of an equally

clueless young wife and unplanned baby. Progress.

Grizzled copy editors sat at a horseshoe table marking up stories

that the slot man, with a sandy handlebar mustache and green-eye-shade,

rolled up and sent pffmmp-clank-clanking up into a ceiling maze of

pneumatic tubes destined for the composing room where rows even more

grizzled, lightening-fingered Linotype operators rendered the news

into lines of hot, silvery lead that clattered from their Rube Goldberg machines. As press time approached, I got to

run last-minute corrections directly back to composing, where the

production man pored over block-type beds that he could read upside

down and backwards. Soon they let me write squibs and fillers. Then I got my byline on a story - a brief, police blotter account about a truckload of molasses spilling on the Hollywood Freeway. After my shift, I took a freight elevator to the cavernous subbasement and climbed out on a catwalk to watch the giant rotary presses printing the edition, glassy-eyed as the sheets whirled by with my little story, somewhere amid the blur of a million copies.

I know. It sounds like a scene out of Ben Hecht's “The

Front Page (1931),” or my favorite film

adaptation of same, Howard Hawks' “His

Girl Friday” (1940) with Rosalind Russell and

Cary Grant.

Of course, it wasn't snappy dialog all the time. There

were spells of tedium. We lived amid the naïve, cold war callus

calculus of the 1950s, its despised materialism, red baiting and

largely unacknowledged discrimination too many thought only happened

down in Dixie. There was only one female reporter in the city room

and her job was the go out and cover “the woman's angle” on

breaking stories. The city room was a sea of white faces that didn't

begin to include black and brown until the mid-1960s.

I feel no nostalgia for the 1950s, during which I spent as much time

as I could reading forbidden texts, trying to be cool in Venice Beach

beatnik coffee houses and watching art house films in French, Italian

and Russian. I don't much like movies about the 1950s, even the good

ones, and few books. I find “Mad Men” too irritating to be

entertaining in the least. I can't help but resent its slick

Hollywood coating of cool that never was.

One thing, though, for all its faults, the L.A. Times of the

1950s – like many of the paternalistic family owned papers of that

day – wasn't corporate in the faceless way we know today. It wasn't

yet infected by Wall Street or Madison Avenue in the way that major

papers, TV and radio stations and big publishing houses owned by

giant communications conglomerates are today. Newspapers then were a

haven for oddballs and misfits, even radicals, not media careerists.

You wore ties, but weren't expected to be conformist – at least not

unless you worked upstairs in advertising, circulation and

accounting. The paper still was the flagship of the Chandler family –

a clan of old time of robber barons invested in the growth of

sprawling Los Angeles to be sure. The family's energetic scion, Otis

Chandler, had just become its publisher, with a burning desire, it

was said, to make it the best paper in the world and plenty of money

to make his dream come true. That set up a competitive dynamic –

prideful to be sure – no longer seen in today's short-term

profit-driven corporate empires.

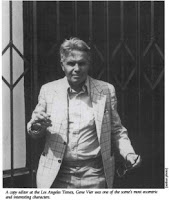

Several of these magnificent misfits came to be among my best friends

as I moved slowly up the

editorial food chain at the Times – most

memorably, the late, exquisitely eccentric writer, copy-editor,

radical and gadfly Gene

Vier. Lots of writers, authors in my circle and

beyond – including Hollywood – have Gene Vier stories. He only

talked to those he liked – had few social graces and never played

office politics. He drove a broken down car, with boxes of

hand-written notes – observations of live, fragments on stories and

books – in the trunk and back seat. He was an often unkept, wiry man with

a greying crew cut, thick glasses and a sometimes annoying nasal

voice, a staccato laugh, and quick wit, a mind for connections, an enthusiastic conversationalist and, most of all, an intent

listener.

|

| Gene Vier |

He had encyclopedic knowledge of literature, politics, history,

theater, films, art and especially, tennis, which he played

devilishly well against various movie actors – only those he

respected – at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. If you said something

particularly insightful, he was known to pull out a notepad from his

pocket and write it down. We used to call him our phantom historian,

picturing future archaeologists someday discovering Gene's notepads

and pondering what they were about. He lived in genteel poverty from

his copy editor salary and a small inheritance from a French-German

family that he never talked about. Peter Falk based his memorable TV series LAPD detective “Colombo”

character on Gene at the suggestion of their mutual friend, director

John Cassavetes, with whom Gene played tennis regularly and hung out

with at the redoubtable West Hollywood hangout, Dan Tana's restaurant on Santa Monica Boulevard.

Gene authored a voluminous history about the Los Angeles Times and its place in the history of

California, plus biographies of tennis greats Bobby Riggs and Don Budge, but he never aspired to fame or fortune. When I first met

him, as a matter of fact, he had been going through a financial

patch, and was secretly living in the Times-Mirror building complex

where we worked. He would do his copy desk shift, go out for dinner,

and hang out with friends, then return to the times after all the

executives had gone home, let himself into the publisher's suite,

shower, brush his teeth and sleep over on the publisher's big leather

couch, slipping out early, just ahead of the big cheeses.

He got away with this for many months – having reached an

understanding with the janitor – until one late night a new

cleaning lady came upon him and screamed, to which the startled Gene

fell off the publisher's couch, yelling for his life. He very likely

would have been dismissed outright in a a 21st century

corporate environment. Instead, he got a only a reprimand and the

employee assistance office helped him find an modest apartment.

I could fill pages about Gene and many of the other characters I

encountered as a stripling writer coming up at the L.A. Times, but

I'll save those for future posts. Many of those remembrances have

found their way into my stories, for example, Our

Own Kind,

my novella of love, politics, newspapering and assassination set in

1968 L.A.

City rooms – those that remain – are carpeted cubicle warrens

nowadays, filled with earnest young

professionals wearing ear buds

clicking their pads and electronic keyboards No time for eccentrics.

A Gene Vier would be as out of place in our contemporary corporate

publishing world as a Linotype machine.

What I find most remarkable, looking back on these experiences, is

the sense of permanence everyone seemed to share in the status quo –

even in the face of daily, possible nuclear obliteration. The

machines, the typewriters, the bells, the wire-photo machine

miraculously transmitting pictures. Imagine! The senior staff had

done things the same way all their working lives, as, it seemed, had

those who preceded them behind those cigarette-burned oaken desks.

The post-war 1950s world may have been changing – what with TV

nationwide, in color, even showing overseas Olympics and British

royal doings.

Little did I realize that I was witnessing a world that was about to

die – and transform even more radically than Gutenberg's press

changed the medieval world. I would spend my adult career, not behind

a clunky Underwood typewriter, but riding a huge rolling wave through

so many changes, one that has deposited me here upon the shores of

digital publishing along with legions of like minded writers around

the world, all of us, at first on the leading edge, then riding the

wave, then becoming mainstream – and still trying to figure it out

as we go along.

Print remains with us, of course, as do paper books, magazines and

newspapers on which I've worked aplenty. Print isn't even mechanical

anymore – except in fine art reproductions. Commercial printing

became a digital process in the 1990s and is now completely so. Books

are rarely, if at all, run off on rotary offset presses. They are

coughed up as needed by super-glorified photo-copy machines

one-at-a-time on demand. The rest, you know, is digital from

conception to writing, to editing, to consuming and reading. And here

we are.

But before I lull myself into thinking that this is it, I have to

remember those clanging teletype machines, and realize that this too

shall morph and morph again, into what will be... One thing, however,

will remain a constant. We still write and we still read. Maybe –

at least until androids start doing so along side us. Then who

knows?

------------------------- -

Umberto Tosi is author of Ophelia

Rising.

Comments

One for our next 'best of blogs' collection, for sure.

While I was a big fan of Mad Men and His Girl Friday, I agree with you about the 50's, not a time I would want to repeat. You embrace NOW with the best of them. This is one of your many strengths, as this essay perfectly illustrates.